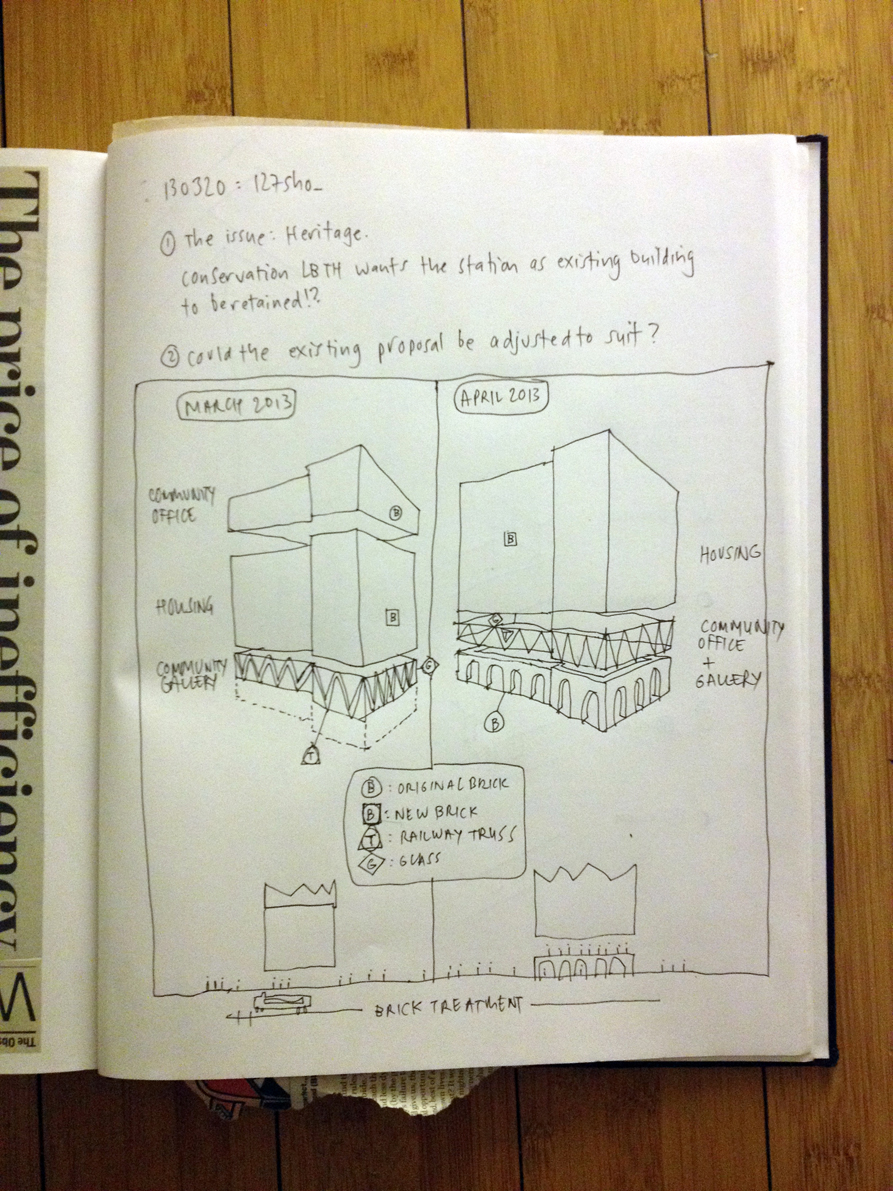

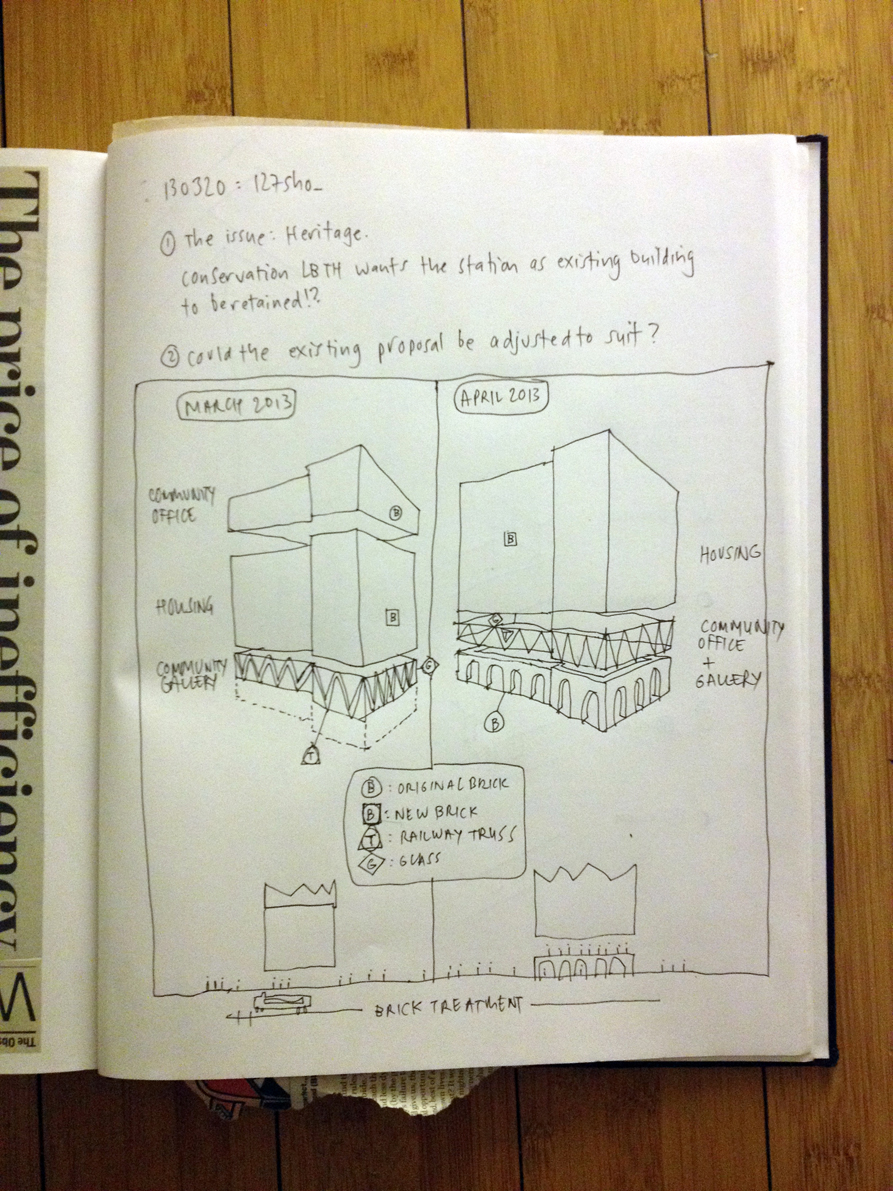

127sho_National Geographic reveals LU

The history of the underground makes us think that the history of Shoreditch Underground Station is one of balancing mobility, housing and infrastructure. Could the architecture of the railway arches be used to support housing: sustainable conservation is in the balance. A re-think is always useful.

000off_WHAT_architecture or resolution?

DRAFT!!

In 1922, one of the possible fathers of modern architecture, Le Corbusier, wrote ‘Architecture ou Révolution: ‘It is the question of building which lies at the root of the social unrest of today; architecture or revolution.’

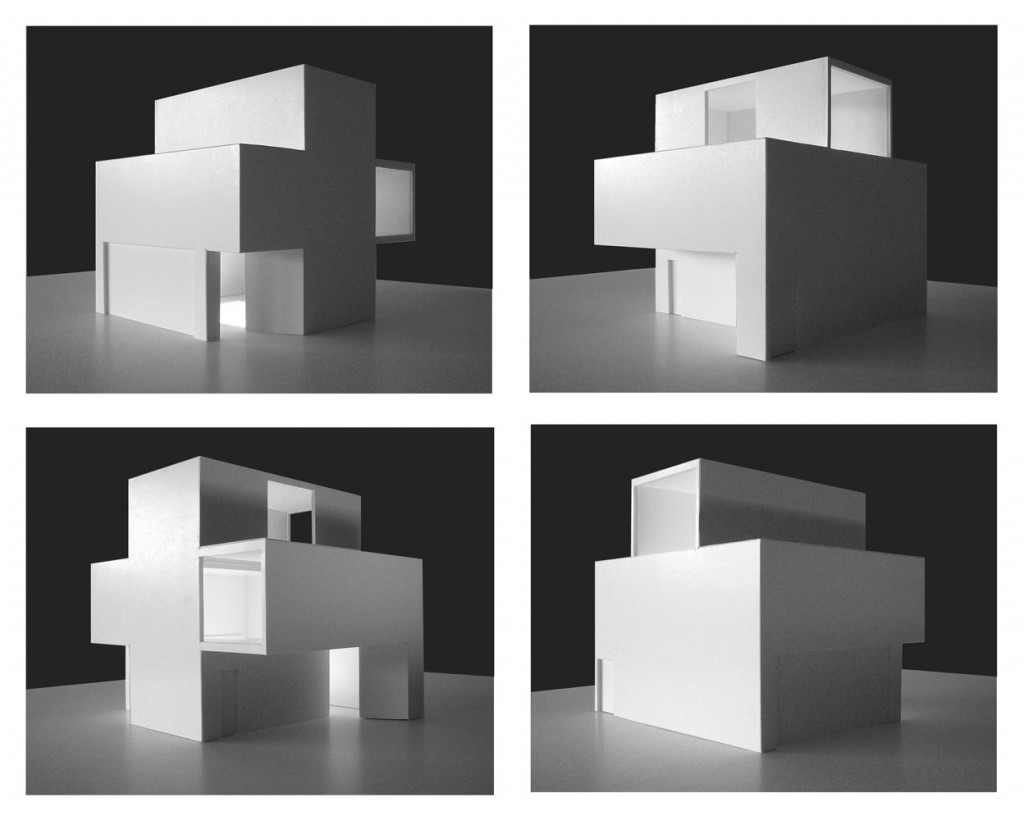

Today, 2013, the question has become WHAT_architecture or resolution!? The society we are today trying to build is one built on image. Buildings as brand: brand building. Nothing new here (Mazda car park by NL Architects, Adidas HQ by Neutelings Reidijk…) but the supplied image is one of increasing resolution. Today your phone can take a better photograph than your camera, 8Mb pixelations of life, then 15Mb…). The image as projected by advertising, architecture and presented in competitions require immense resolutional demands 300dpi… I saw a 1GB photoshop file on the server …’8-bit’ attitudes whereby….

072hin_FROM MARITIME TO MAORITIME: TE HONO KI AOTEAROA

Karl Burrows and Anthony Hoete introduce the Birkbeck screening of: Te Hono Ki Aoteroa, a ‘waka taua‘, or maori war canoe made from a 800 year old NZ native tree. The waka taua was built for the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, Holland.

In Maori culture, artefacts are treated as living entities not museum pieces: historic canoes are paddled not hung from walls. In Britain, a nation with a long and proud maritime history, increasingly old ships are not kept afloat and, as The Guardian has reported, the Cutty Sark was “dead even before she went up in flames” in 2007. Today the Cutty Sark is held in dry dock suspension and conservation in the Western sense is thus more akin to preservation. The Maori understanding and treatment of heritage is unique (horitage) for its sees heritage as being alive and this represents a decolonisation of conservation.

There is also an anecdotal relationship between the maori meeting house Hinemihi (Grade 2 Listed Building sitting in Clandon) and a waka taua. Maori culture is steeped in mythology and the sighting of a phantom war canoe on Lake Tarawera in 1886 was an omen, a sign of death to all who saw it. The apparition was widely discussed and Maori consulted their tohunga, Tuhoto Ariki, who foretold a disaster would overwhelm the area. Mount Tarawera erupted.

The documentary Te Hono Ki Aoteroa has undisputed localised cultural value (for Maori, NZers, maritimologists?..) yet the distant event of cutting down a 800 year old tree and its chain-saw and chisel conversion into a naval vessel also raised some questions in relation to both boat and building heritage:

Karl Burrows and Anthony Hoete introduce the Birkbeck screening of: Te Hono Ki Aoteroa, a ‘waka taua‘, or maori war canoe made from a 800 year old NZ native tree. The waka taua was built for the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, Holland.

In Maori culture, artefacts are treated as living entities not museum pieces: historic canoes are paddled not hung from walls. In Britain, a nation with a long and proud maritime history, increasingly old ships are not kept afloat and, as The Guardian has reported, the Cutty Sark was “dead even before she went up in flames” in 2007. Today the Cutty Sark is held in dry dock suspension and conservation in the Western sense is thus more akin to preservation. The Maori understanding and treatment of heritage is unique (horitage) for its sees heritage as being alive and this represents a decolonisation of conservation.

There is also an anecdotal relationship between the maori meeting house Hinemihi (Grade 2 Listed Building sitting in Clandon) and a waka taua. Maori culture is steeped in mythology and the sighting of a phantom war canoe on Lake Tarawera in 1886 was an omen, a sign of death to all who saw it. The apparition was widely discussed and Maori consulted their tohunga, Tuhoto Ariki, who foretold a disaster would overwhelm the area. Mount Tarawera erupted.

The documentary Te Hono Ki Aoteroa has undisputed localised cultural value (for Maori, NZers, maritimologists?..) yet the distant event of cutting down a 800 year old tree and its chain-saw and chisel conversion into a naval vessel also raised some questions in relation to both boat and building heritage:

- in order to carve a canoe, how do you get a 4-tonne log out of the forest?

- how much did Te Hono Ki Aoteroa cost and who paid?

- how did Te Hono Ki Aoteroa get to Europe? We imagine a war canoe being loaded onto an Air NZ 747 to become a flying boat as fantastical…

- with reference to Great Fleet Myth, how would a canoe with such a minimal freeboard stay afloat in the turbulent South Pacific oceanic currents? In the documentary Te Hono, waka rangatira Hekenukumai Busby offered some lucid bush science when commenting that 800 year opld trees weather and ager asymmetrically such that the “heart of the tree is not in the centre”. The heart of a tree, like the human heart, is displaced. The cross-sectional rings of a tree denote not only age but also an asymmetric density. If the log is cut correctly this will provide stable buoyancy to the canoe as the heavier part of the log naturally turns and orientates like a keel when put to water…