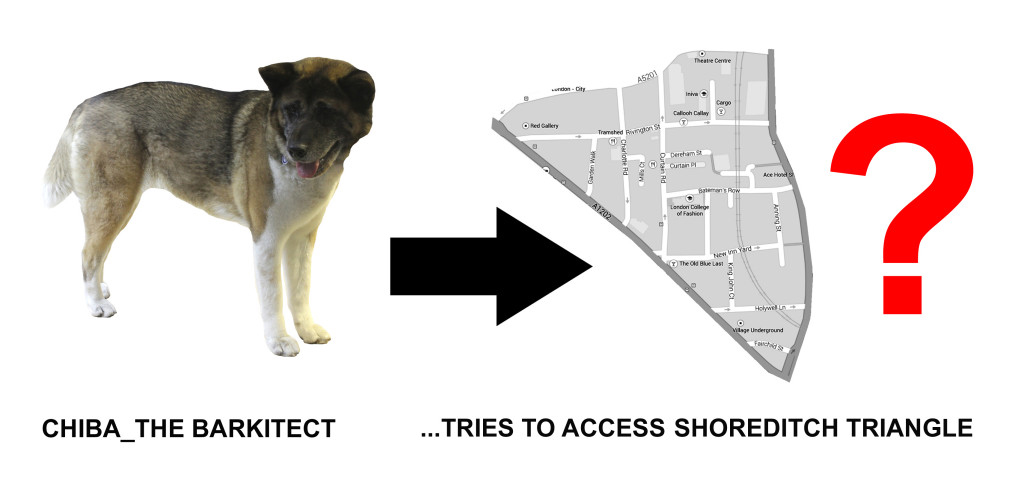

237dog_GAME OF CANINE ACCESSIBILITY

Chiba, our Japanese Akita rescue dog and a roving ‘barkitect’ sniffs out spaces of interest in Shoreditch… C,,–,,> The Game of Barkitecture is one of identifying canine access. Under the Clean Neighbourhood and Environment Act 2005, local authorities were given the power to introduce Dog Control Orders (DCOs) in order to address dog related issues in open spaces. The DCOs can include dog exclusion orders, dogs on lead orders, dogs on lead by direction orders, removing dog foul orders and orders limiting a number of dogs walked by one person. Any proposed DCOs must be advertised for consultation in local newspapers. Whilst no record is held regarding how many DCOs have been implemented in England and Wales, access officers in local authorities have indicated that there has been an increasing amount of restrictions placed on dog owners every year. This trend has impacted on dog walkers, some of whom have been dispersed onto sensitive land which has caused wider negative effects to both plant and animal life, and thereby causing further restrictions being placed on dogs and their owners. From October 20th 2014, Public Spaces Protection Orders (PSPOs) will be introduced under the Anti-social behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 and will replace DCOs. The local authorities will have similar powers to introduce orders, except there will be no requirement for them to advertise PSPO consultations in local newspapers. So our pet subject is: What is the law on allowing dogs in bars, restaurants and shops? The difference in attitudes to dogs in commercial establishments between say Germany (where dog friendliness ranks above child friendliness) and the UK is cultural rather than legal. There is no British law that prevents a dog entering a premise – it is at the discretion of the landlord. There is a gross misconception in the UK that dogs are not allowed in places where food is served: this is not the case. The only legal obligation on the owner is to make sure there is no risk of contamination and that all food preparation areas are up to specified hygiene standards. So with this in mind we took Chiba along to our local butcher’s Brian Roberts (Peckover Traditional Butchers) which was awarded a Food Hygiene Rating of 4 (Good) by the local Council in 2015 – presumably not a 5 because the sight of a dog in a butcher’s shop still raises an eyebrow or two. The Kennel Club’s Open for Dogs Campaign aims to persuade more UK businesses to be dog-friendly. Each year there is a competition to find the most dog-friendly, with the winners announced at the Discover Dogs…

Chiba, our Japanese Akita rescue dog and a roving ‘barkitect’ sniffs out spaces of interest in Shoreditch… C,,–,,> The Game of Barkitecture is one of identifying canine access. Under the Clean Neighbourhood and Environment Act 2005, local authorities were given the power to introduce Dog Control Orders (DCOs) in order to address dog related issues in open spaces. The DCOs can include dog exclusion orders, dogs on lead orders, dogs on lead by direction orders, removing dog foul orders and orders limiting a number of dogs walked by one person. Any proposed DCOs must be advertised for consultation in local newspapers. Whilst no record is held regarding how many DCOs have been implemented in England and Wales, access officers in local authorities have indicated that there has been an increasing amount of restrictions placed on dog owners every year. This trend has impacted on dog walkers, some of whom have been dispersed onto sensitive land which has caused wider negative effects to both plant and animal life, and thereby causing further restrictions being placed on dogs and their owners. From October 20th 2014, Public Spaces Protection Orders (PSPOs) will be introduced under the Anti-social behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 and will replace DCOs. The local authorities will have similar powers to introduce orders, except there will be no requirement for them to advertise PSPO consultations in local newspapers. So our pet subject is: What is the law on allowing dogs in bars, restaurants and shops? The difference in attitudes to dogs in commercial establishments between say Germany (where dog friendliness ranks above child friendliness) and the UK is cultural rather than legal. There is no British law that prevents a dog entering a premise – it is at the discretion of the landlord. There is a gross misconception in the UK that dogs are not allowed in places where food is served: this is not the case. The only legal obligation on the owner is to make sure there is no risk of contamination and that all food preparation areas are up to specified hygiene standards. So with this in mind we took Chiba along to our local butcher’s Brian Roberts (Peckover Traditional Butchers) which was awarded a Food Hygiene Rating of 4 (Good) by the local Council in 2015 – presumably not a 5 because the sight of a dog in a butcher’s shop still raises an eyebrow or two. The Kennel Club’s Open for Dogs Campaign aims to persuade more UK businesses to be dog-friendly. Each year there is a competition to find the most dog-friendly, with the winners announced at the Discover Dogs…

179prs_YOU’VE GOT TO BE IN TO WIN: BUT IS IT WORTH IT?

179prs_The imagination game_Practice Based Research

“In one of the many, many, brilliant presentations at the RMIT Practice Research Symposium, practitioner and teacher Alisa Andrasek mentioned a scene in the movie The Imitation Game, where Alan Turing calculates the incomprehensible number of years it would take for a human to break a single piece of code. This scale of design was actually visible in her research images, from Turing’s cables on: astonishing pictures of information at exponential scale, giving a tangible, visual sense of the scale of intelligence accelerated through intelligent design. It feels like what’s going on at the Practice Research Symposium (PRS) on architectural practice.

I’ve just come back from Barcelona, where I was attending my third PRS, the PhD programme for practising architects to develop their real work as research, and on each occasion, I’ve been aware of an of exponential shift in scale. That is, the scale in the actual nature of the work going on; in this vast research into how architects actually think, work, design, communicate, refine, produce, reference, share, criticise and develop their work, individually and collectively. But also a shift in scale in my struggling, feeble attempts to perceive the scope of this extraordinary invention; in the startling step changes in the individual work of the already high-level practitioners on this programme; and in the composite growth of intelligence which it is generating throughout its whole booming community. OK, I’m a really big fan.

Information at an exponential scale from Alisa Andrasek

The PRS is an evolution of architectural design work, with all its projects, representations, crit structures, buildings, references, trips, forms of dissemination, development and improvement taken to PhD level. It was invented by Leon van Schaik, innovation professor at RMIT (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology), who 25 years ago, found a body of excellent architects working in Melbourne, with a highly evolved community of real architectural practice, but no professionally or academically sanctioned way of talking about it, and almost no international profile.

He developed this first through a Masters in Architecture programme, which brought architect practitioners back to university, developing their ability to describe, understand, and do their work better. The quality and status of the Melbourne architectural scene is a direct outcome of this academic process.

Then it developed into an international PhD programme. Now under the leadership of Richard Blythe, it is oversubscribed with more than 150 candidates enrolled worldwide. It is currently extending through ADAPT-r (Architecture, Design and Art Practice Training-research – a definite analogy with electrical plugs), an EU-funded start-up strategy for European partners to set up their own versions. You can enroll on versions of this programme via Aarhus, Ghent Sint Lucas, the Estonian Academy of Arts, the University of Ljubljana, and – coming soon – the University of Westminster, the Mackintosh and Queens University Belfast.

What this means is that practitioners of any kind – sole practitioners, substantial firms, old, young, arty types, practice innovators, poets, teachers, skilled working grafters – get a specially made, retailored, academically approved (and wow, is that bit tough) responsive, academic and demanding programme to identify, examine and improve the tactics they are already using to design.

In this it is surfacing what van Schaik calls tacit information – our incredibly sophisticated constructions (in both senses) of drawings, pictures, references and skills; our abilities to see, read and compose things; to work them out technically and enable them financially; our projective visualisations and testing of possible futures; the leaps of imagination between disciplines and things that are, frankly, undisciplined – or at least, largely uncharted, such as spatial sense and social interaction. In our concerted use of an agile, collective spatial intelligence, we seem as a community to be way ahead of the game.

All of this is visible and engineered in the PRS weekend events. These are great big, super-rigorous cross-crit events, which candidates attend twice a year. They are held in Europe (Barcelona and Ghent) as well as Melbourne and Ho Chi Minh City, so with good air travel you should be able to reach two somewhere. Each PRS includes presentations of ongoing work, exams, candidate training and supervisor training (itself a sort of developing feedback loop), but they are clustered in terms of importance around the weekend, so that the most possible people can get to the most possible events.

The final exams are carefully designed constructions in themselves. They are composed of three elements: an exhibit or installation of the PhD in physical form; a catalogue or written text (which by itself would get a PhD in many places); and a presentation and debate of the work with the examiners, which is recorded. The three components are read jointly in their collective ability to deliver the architectural research at PhD level.

The staging is public, rehearsed and consummate. In Barcelona, three people were completing their PhDs. Tania Kalinina and James McAdam’s reshaping of the conditions of post-Soviet Russia for ‘normal’ architectural practice was discussed within the public/professional spaces of Barcelona’s modernist College of Architects. Riet Eeckhout completely refocused the same space for working analysis of her beautiful and instinctive process drawing work.

But the work-in-progress presentations on the Saturday and Sunday are the real core of the system. You get to see the most astonishing work of all kinds, next to each other and the startling step changes in them at each time, as privileged participants in the best crits in the world. I’m totally gripped.

Under this system, John Brown’s work on private houses in Calgary, Canada, has turned into an amazing new form of adaptable, off-the-peg, mass housing. Its marketing is as integral to its design as that of Apple. Some more recent candidates’ digital work seeks to question the fast but solidly formal conventions and discourses that have emerged around ‘parametric’ design. Other working prejudices have been exposed by Alan Higgs, whose stubborn refusal to bow to established conventions means his strong work, mainly for wealthy clients, falls off the visible spectrum of old-style publishability. Then there is the amazing richness and variety of the Irish scene: TAKA, Steve Larkin, Boyd Cody, and the extraordinary and little-known colour field, immersive, highly social buildings of McGarry Ní Éanaigh. And that’s just a sample.

This highly evolved, delicate, responsive PRS system ruthlessly exposes itself to our blundering criticisms, both for its own benefit and for ours

This programme has strict disciplines, which are themselves constantly being refined, tested, redeveloped, grown to a new level (and sometimes, accidentally broken) in relation to the fundamental respect for improvisational thought which this process seeks to nurture, develop and improve. There are fundamental principles of sharing, of generosity, of inclusivity, of being positive in your criticism, and of suspending your prejudices about others’ tastes and methodologies. There is the absolute –but truly challenging – need to retain respect and care for others, and the work they have so carefully achieved, while improvising madly yourself. Even the hospitality, down to the carefully designed catering, is delicately managed to allow the greatest number of unforeseen connections to take place in this astonishing new community.

Because this, like architecture itself, is an essentially collective structure, formed through unique but recognisable activities. So maybe from some of the very first cultural constructs (shelter, society) comes the way we put information together – history, technology, building references, spatial awareness, working practices, representation in theory and practice, art, science, instinct, conviviality, imagination, craft, discipline and instinct – to produce our special projective discussions of how an idea is manifested and tested. There may of course be some elements of an occasional sense of demurral from professors visiting from other more established disciplines. But there is also a sense of awe at the sheer toughness of a system that, to us, seems like a more intense, academic and better form of normal; of the ways we really work.

This highly evolved, delicate, responsive PRS system ruthlessly exposes itself to our blundering criticisms, both for its own benefit and for ours. Our trip-ups at the plenary session engendered salutary responses from both Alan Higgs (candidate) and Richard Blythe (dean at RMIT), batting back our attention to the scale, care, detailed resolution and fragility of this astonishing and growing invention. Rules and their removal both have creative power, and it is tough and astonishing to configure and expand this in an academic context, when it is, by definition, work in progress.

Unlike the star system through which architecture is usually represented, this system is about working collectively, imaginatively, hopefully and with respect for others. It’s like architecture at its best. As van Schaik argues, the size, type and nature of such communities really matters. The architectural scene in Melbourne, like Dublin, seems to work in a very pure way, which makes it a petri dish for this kind of community. The immense care which is taken to link these up, share and develop them and expand outwards, within a whole multiplicity of academic systems, is a work of astonishing exponential and brilliant design in itself.

So watch out for anything that seems odd or difficult; it probably really matters. Even the symposiums’ determined adherence to acronyms is surely part of this care. Like Cedric Price’s portacabins, they are important for what they don’t do. Those portacabins really weren’t pretty. You were supposed to want to clear them away once they weren’t working. The PRS is not a catchy title. You don’t get a three-word definition of what this is ; you have to really work at it. This is very, very pure research, into a very imperfectly charted territory of sophisticated human activity, evolving with immense care, discipline and generosity. Pay attention. You won’t regret it.

000off_WHAT_architecture #Pimpmychair

Upholsterers: Anna Szymanska, Fadime Yasar and Anastassia Zamaraeva. 'How to denimise a chair' - Denim Manual graphic by Anastassia Zamaraeva.

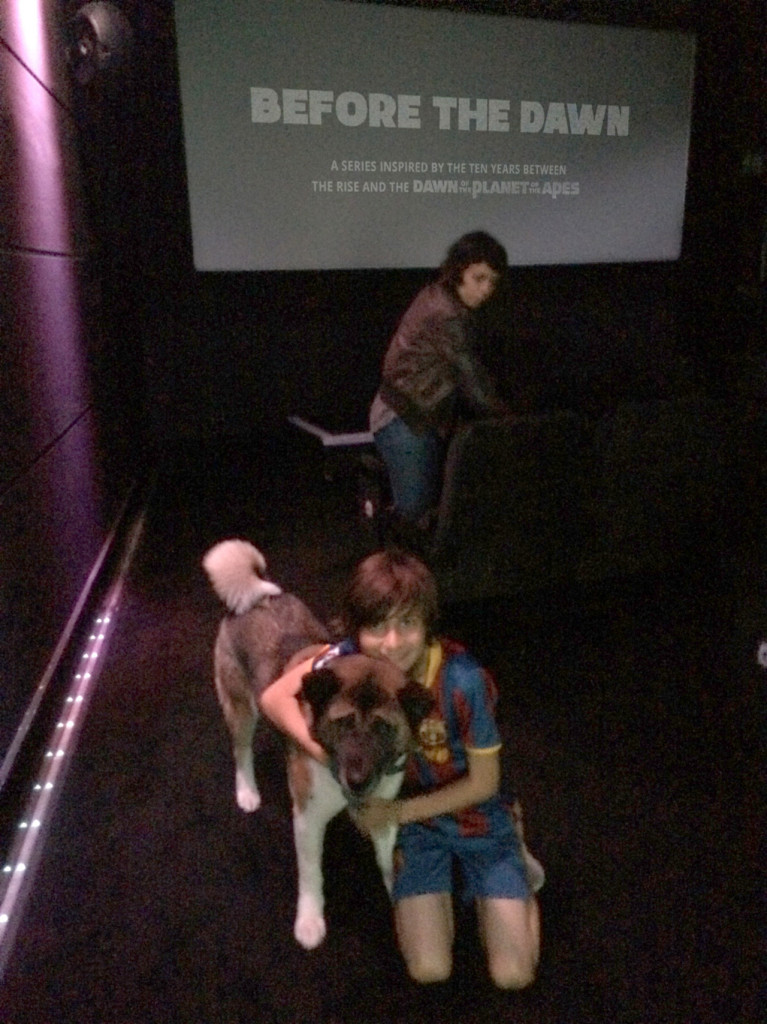

237dog_THE HAPPY BARKITECT

Chiba: the Barkitect. The office doge. We’re often told she looks sad. But in reality she has ‘panda eyes’: dark hair surrounds. What if the hair around her eyes was blonde? Would she look happier: do or dye!

Chiba: the Barkitect. The office doge. We’re often told she looks sad. But in reality she has ‘panda eyes’: dark hair surrounds. What if the hair around her eyes was blonde? Would she look happier: do or dye!

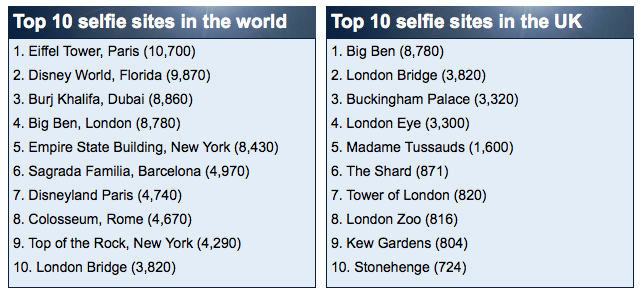

048per_Architecture as Selfie backdrop

127sho_NORTON FOLGATE: AN IMAGE OF DESTRUCTION

Please add your name to the illustrious list of those calling for a Public Inquiry by writing direct to the Secretary of State. The Spitalfields Trust suggest you include the following points in your letter which you can email to gregclarkmp@parliament.uk or post to House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA

This is not just a very important case for London, it is also of national importance and has serious implications for Conservation Areas across the country.

This fragile Conservation Area is protected by local Conservation Guidelines, which this application disregards.

The vitality of the City does not depend upon demolishing some warehouses in Spitalfields.

The democratic decision at a local level has been over-ruled by the centralised intervention of the Mayor of London.

The Spitalfields Trust’s Conservation Scheme for Norton Folgate is independently costed and is viable. It could be delivered more quickly and far more cheaply than that proposed by British Land. It is based upon the repair of the existing historic buildings, with sensitive infill of empty sites in keeping with the Conservation Area.

The Spitalfields Trust’s scheme would provide more affordable business accommodation, particularly for small businesses and provide more housing, both low cost and private, for the local borough.

This case has given rise to substantial local and national controversy, and has been widely covered in the media.

The whole-scale demolition of heritage assets in the Conservation Area conflicts fundamentally with national policies as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework in section 12 in relation to conserving and enhancing the historic environment.

Please add your name to the illustrious list of those calling for a Public Inquiry by writing direct to the Secretary of State. The Spitalfields Trust suggest you include the following points in your letter which you can email to gregclarkmp@parliament.uk or post to House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA

This is not just a very important case for London, it is also of national importance and has serious implications for Conservation Areas across the country.

This fragile Conservation Area is protected by local Conservation Guidelines, which this application disregards.

The vitality of the City does not depend upon demolishing some warehouses in Spitalfields.

The democratic decision at a local level has been over-ruled by the centralised intervention of the Mayor of London.

The Spitalfields Trust’s Conservation Scheme for Norton Folgate is independently costed and is viable. It could be delivered more quickly and far more cheaply than that proposed by British Land. It is based upon the repair of the existing historic buildings, with sensitive infill of empty sites in keeping with the Conservation Area.

The Spitalfields Trust’s scheme would provide more affordable business accommodation, particularly for small businesses and provide more housing, both low cost and private, for the local borough.

This case has given rise to substantial local and national controversy, and has been widely covered in the media.

The whole-scale demolition of heritage assets in the Conservation Area conflicts fundamentally with national policies as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework in section 12 in relation to conserving and enhancing the historic environment.