003LAU_TEMPLE OF LAUGHTER

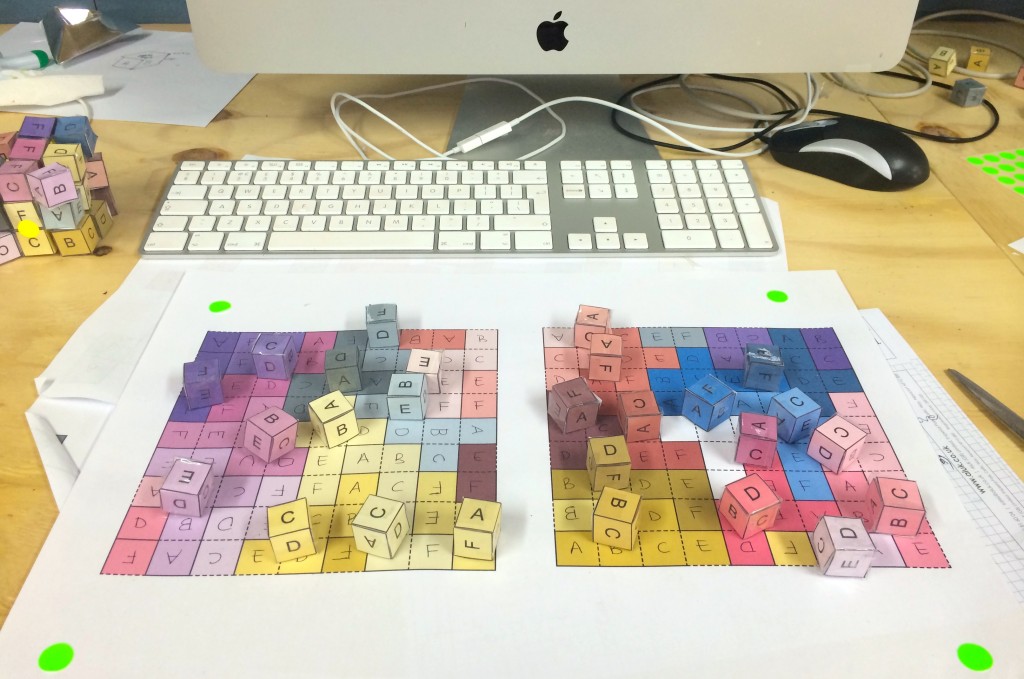

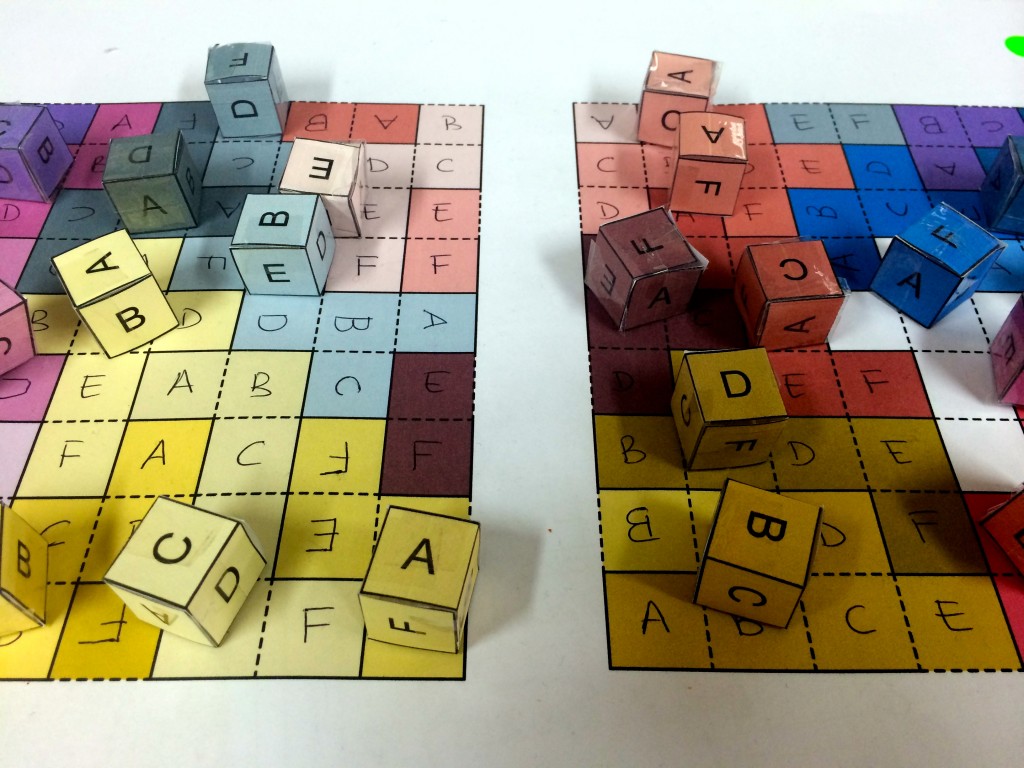

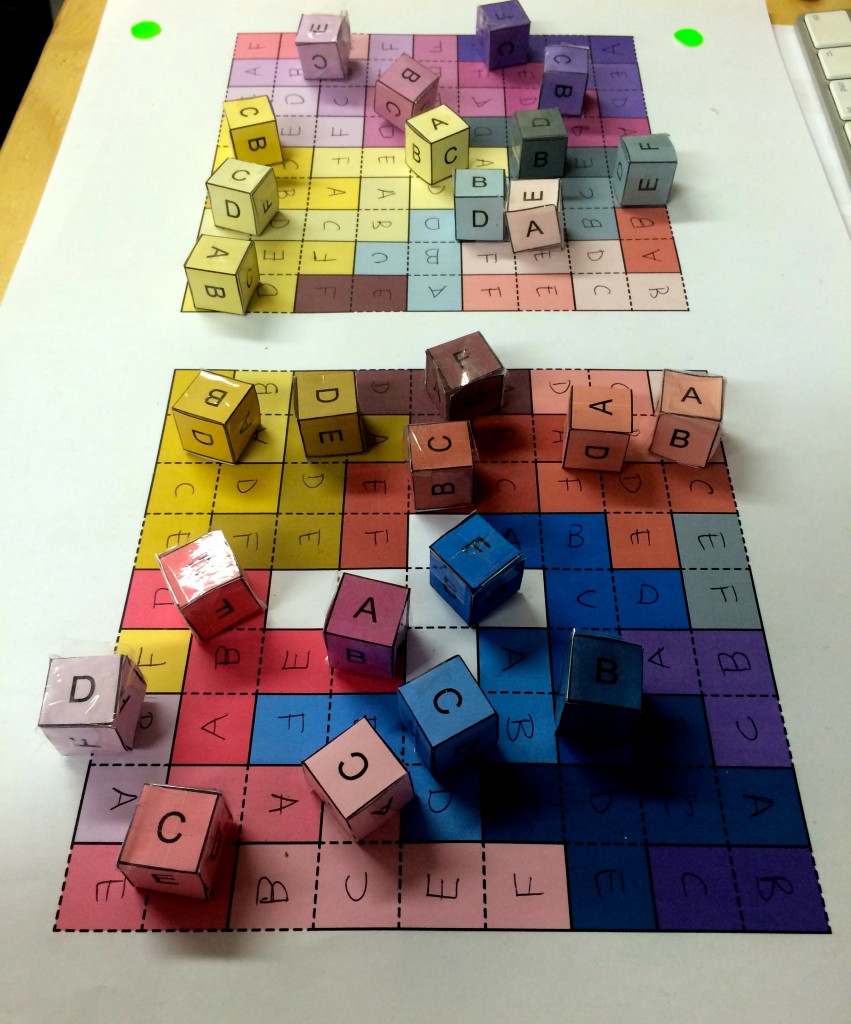

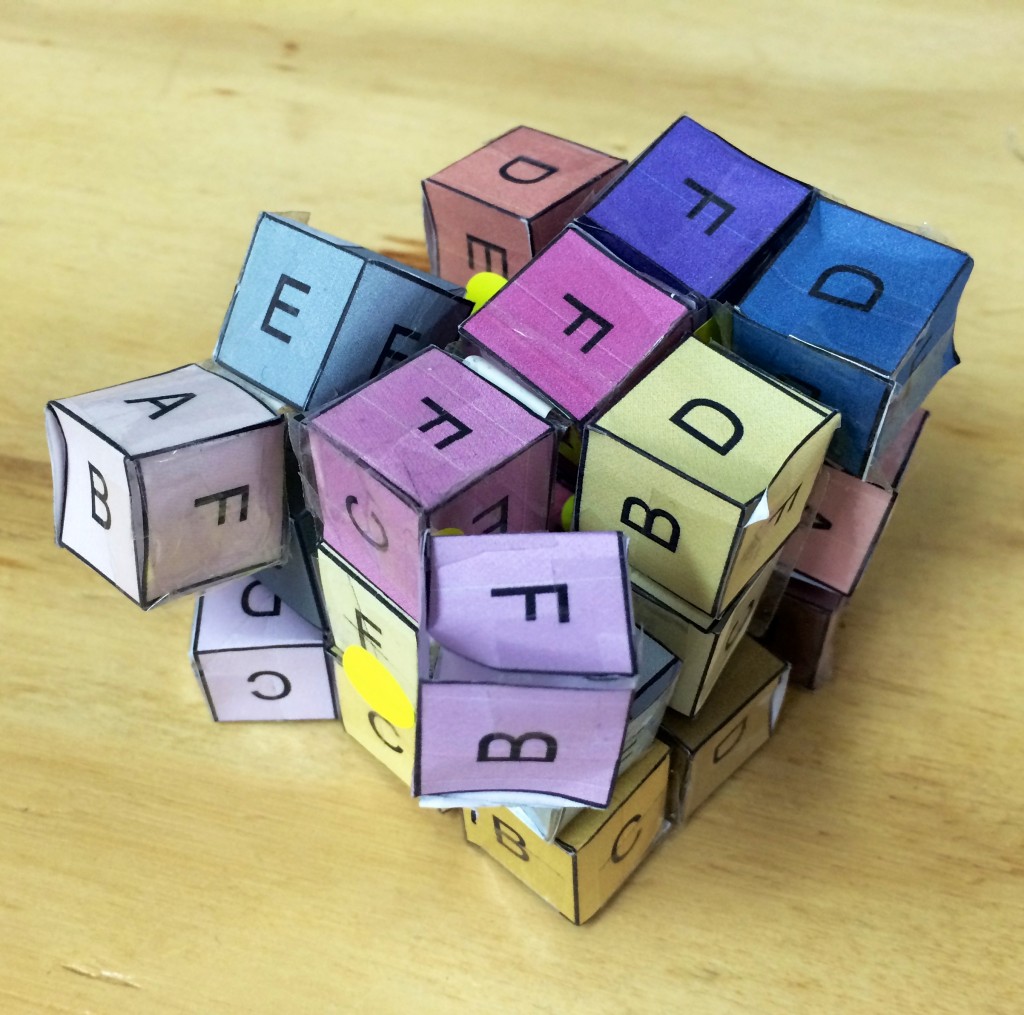

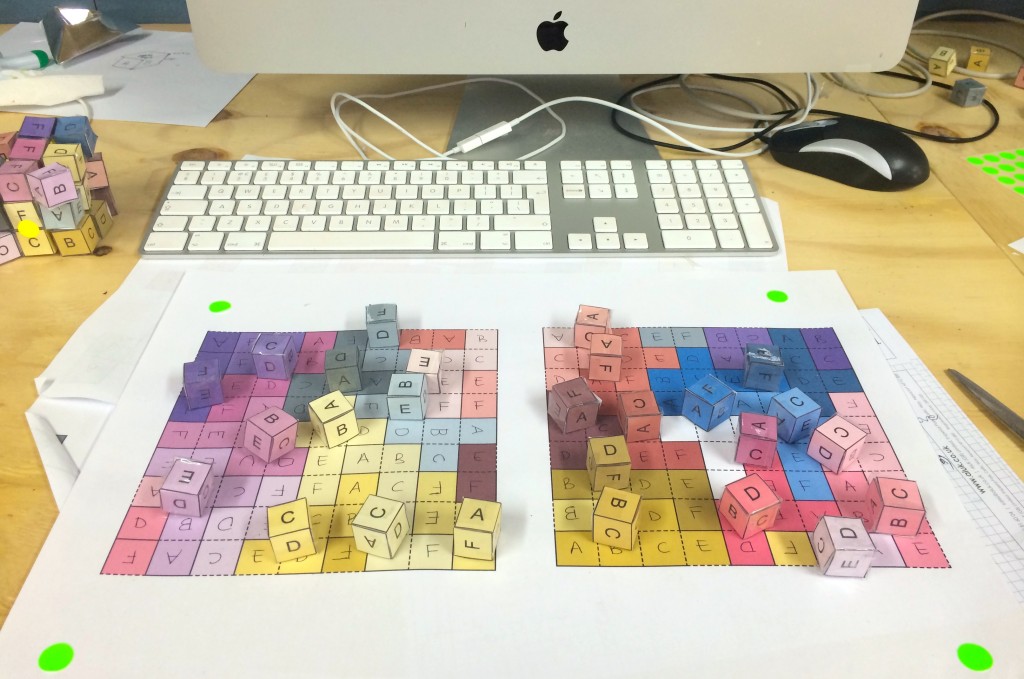

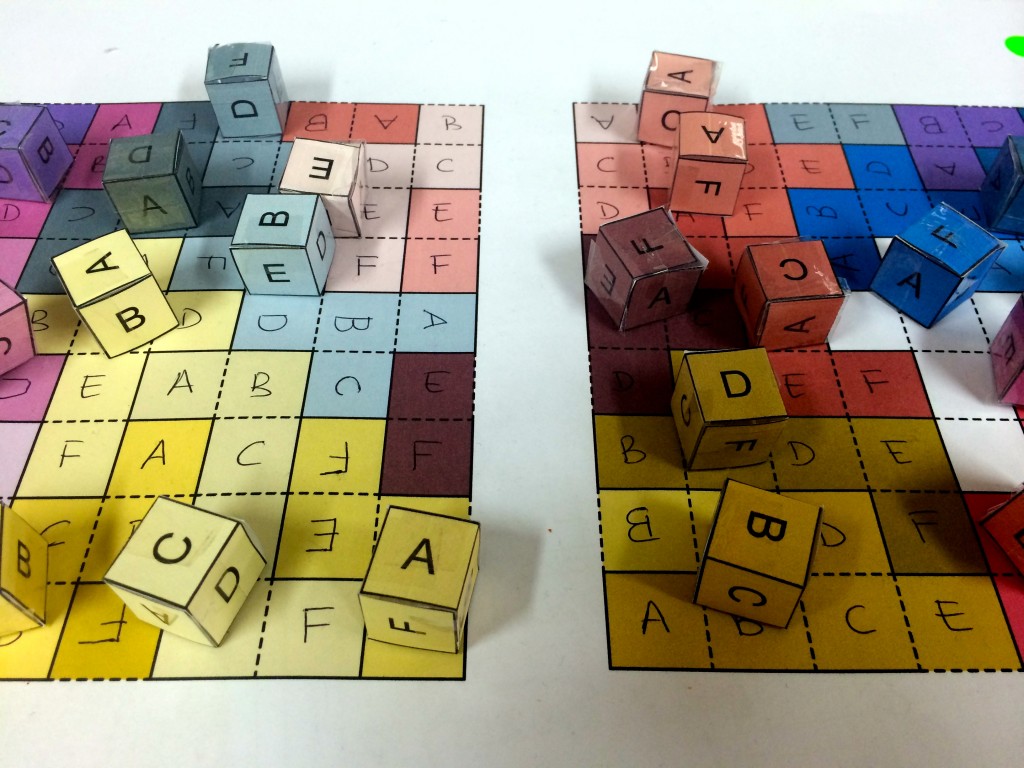

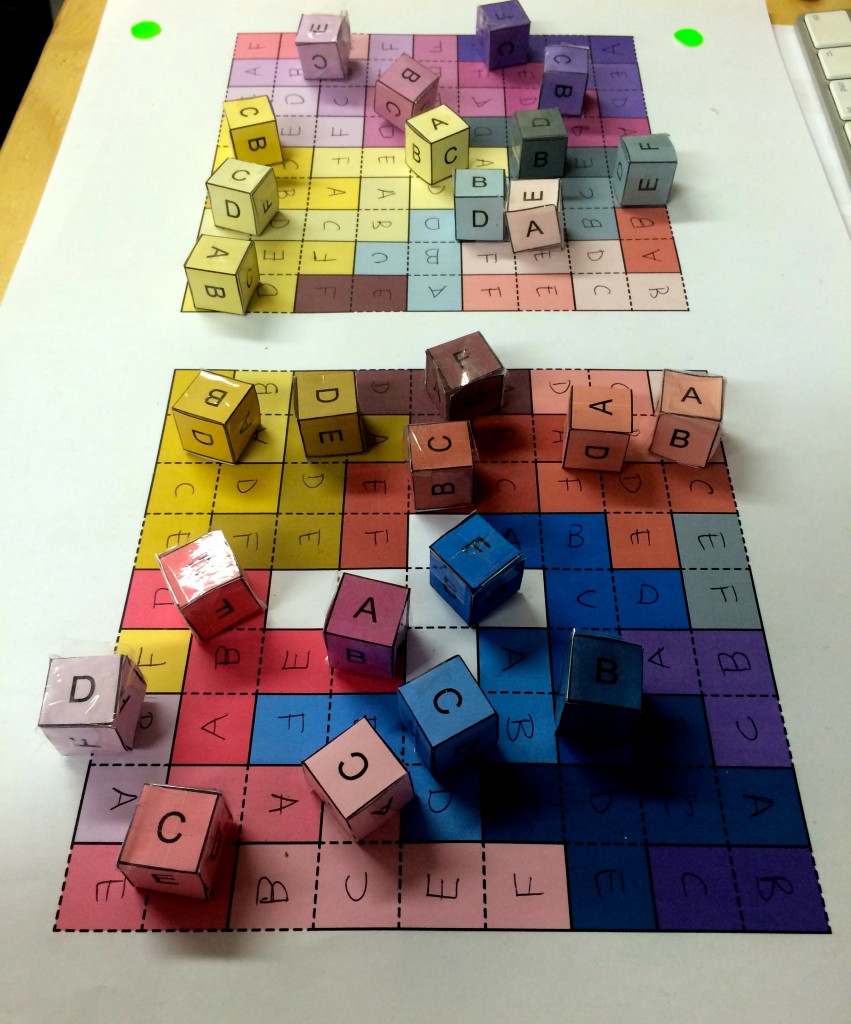

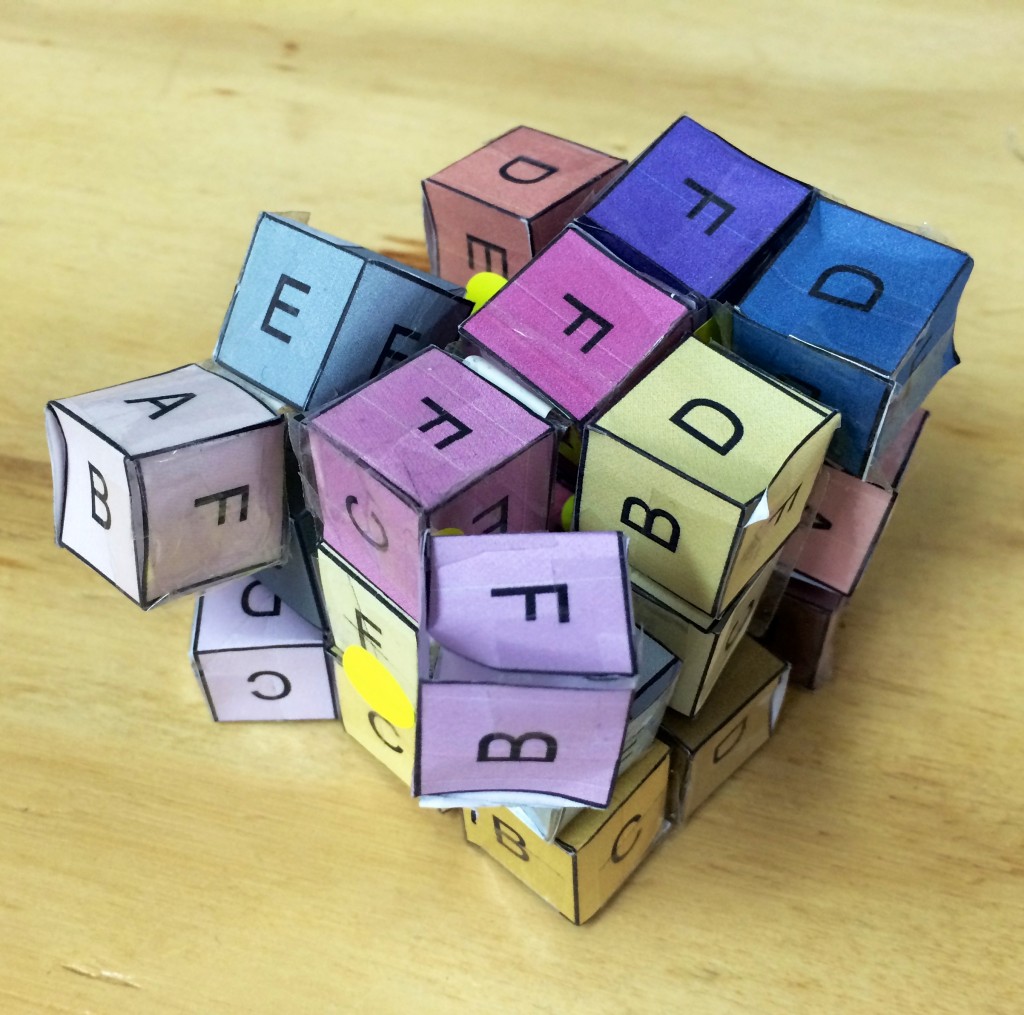

The Temple of Laughter was a pioneering project for The Game of Architecture in the sense that it played with the rules of the architectural competition. As the submission requirements called for a drawing and a model this raised the possibility: could the drawing literally build the model?

This action would be confrontational as it would, for example, render architectural representation pointless. In architectural culture, the architects’ drawings are the principle design tool conveying information ranging from ideological expression through to construction detailing. Yet with the Temple of Laughter the drawing was purely a 2d plane emptied of all information such that the drawing was now a flat geometric plan(e) awaiting transformation, origami-like, into a three dimensional form. The question was how could we work out the geometrical puzzle that would allow this to happen? WHAT_Architecture used a hybrid “8-bit parametricism” of part-analogue (paper), part-digital (computer) modelling to crack the problem.

This action would be confrontational as it would, for example, render architectural representation pointless. In architectural culture, the architects’ drawings are the principle design tool conveying information ranging from ideological expression through to construction detailing. Yet with the Temple of Laughter the drawing was purely a 2d plane emptied of all information such that the drawing was now a flat geometric plan(e) awaiting transformation, origami-like, into a three dimensional form. The question was how could we work out the geometrical puzzle that would allow this to happen? WHAT_Architecture used a hybrid “8-bit parametricism” of part-analogue (paper), part-digital (computer) modelling to crack the problem.

This action would be confrontational as it would, for example, render architectural representation pointless. In architectural culture, the architects’ drawings are the principle design tool conveying information ranging from ideological expression through to construction detailing. Yet with the Temple of Laughter the drawing was purely a 2d plane emptied of all information such that the drawing was now a flat geometric plan(e) awaiting transformation, origami-like, into a three dimensional form. The question was how could we work out the geometrical puzzle that would allow this to happen? WHAT_Architecture used a hybrid “8-bit parametricism” of part-analogue (paper), part-digital (computer) modelling to crack the problem.

This action would be confrontational as it would, for example, render architectural representation pointless. In architectural culture, the architects’ drawings are the principle design tool conveying information ranging from ideological expression through to construction detailing. Yet with the Temple of Laughter the drawing was purely a 2d plane emptied of all information such that the drawing was now a flat geometric plan(e) awaiting transformation, origami-like, into a three dimensional form. The question was how could we work out the geometrical puzzle that would allow this to happen? WHAT_Architecture used a hybrid “8-bit parametricism” of part-analogue (paper), part-digital (computer) modelling to crack the problem.

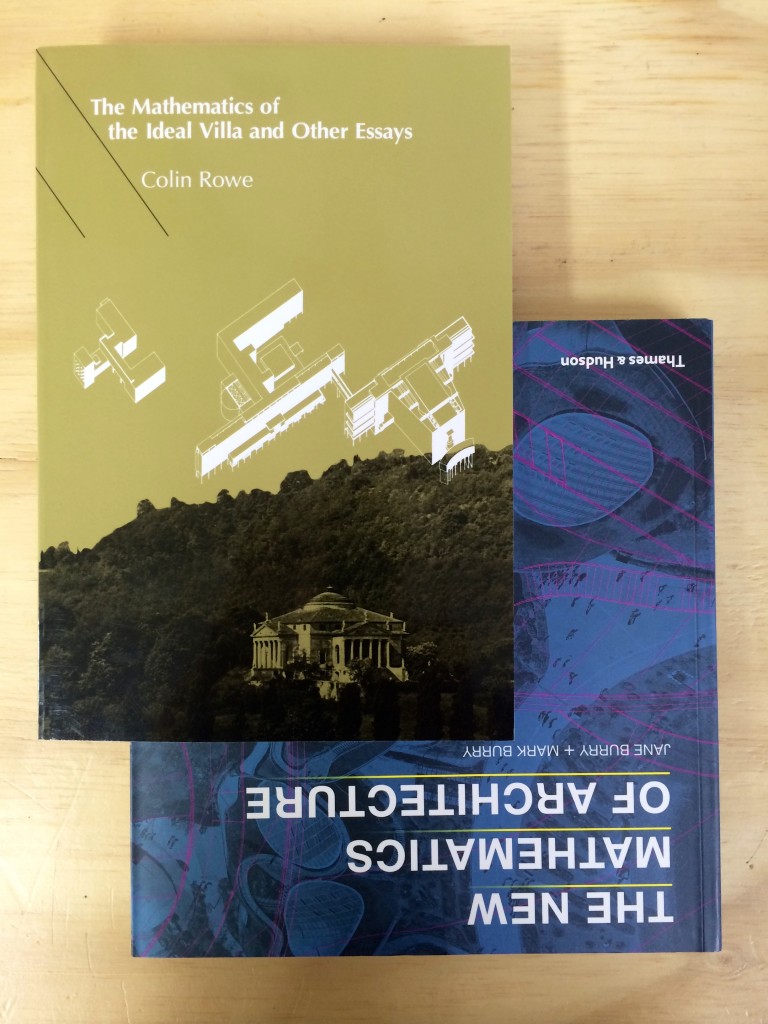

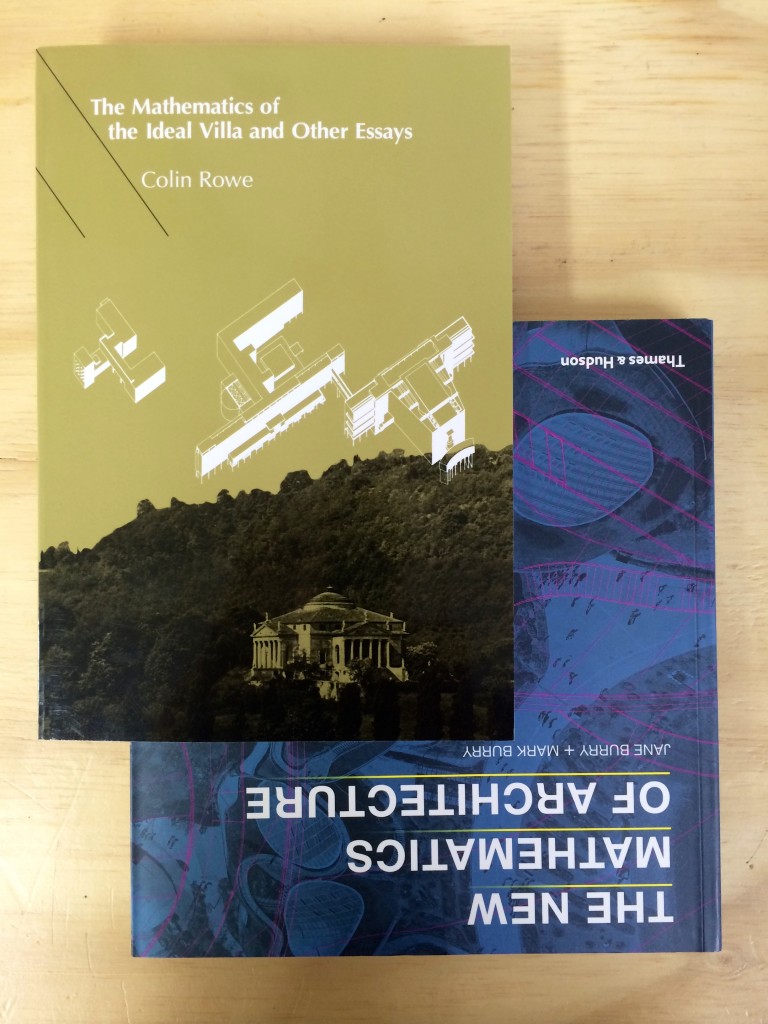

179prs_Cross-reading: architectural theory as mash-up!

In the same way as Radio Soulwax (2ManyDjs) adeptly mashed two songs seamlessly together, it is not uncommon to read two (or more) books at the same time. If architectural theory accommodated a critical mash-up this would lead to counterpoint and cross-reading! To that end I am currently cross-reading… Colin Rowe’s “The Mathematics of the ideal Villa and Other Essays” from 1947 (which compares the design of geometric proportioning in the work of Palladio and Le Corbusier) with Mark and Jane Burry’s The New Mathematics of Architecture from 2010 (which observes digital design in architectural morphology). What does this mash-up cross-reading avow? In a sentence: a mathematical shift from abstract volumetrics to complex surfaces.

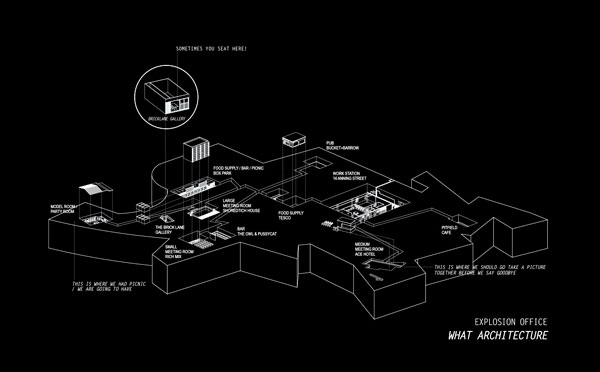

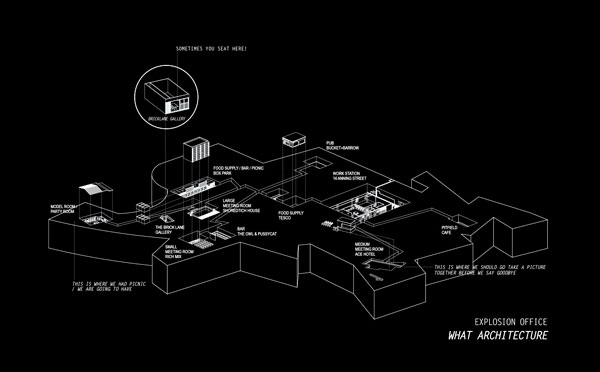

000off_TIME FOR TEA

Akin to traditional Tokyo living where many domestic functions were located outside the house (bath house, okonomiyaki kitchens…), the current WHAT_office is an ‘exploded’ office. Exploded in the sense that our three client spaces are located just outside the office. All three ‘Meeting Rooms’ needless to say are dog friendly:

- Meeting Room A: Ace Hotel, 100 Shoreditch High Street;

- Meeting Room F: the Forge and Co. at 154 Shoreditch High Street

- and finally Meeting Room T: at Time For Tea which is cryogenically frozen in time: that is the 1920s. Local resident Dan Cruickshank, the art historian, BBC TV presenter and architectural chronicler reports on Meeting Room T Johnny Vercoutre’s preservation project on Spitalfield’s Life.

179prs_AND THE LOSER IS… IT’S NOT THE WINNING, IT’S THE PLAYING OF THE GAME OF ARCHITECTURE.

We have often asked on blablablarchitecture: if WHAT_architecture awarded an architectural prize what or to whom would it be for? The RIBA has a client Award recognising “the key role that a good client plays in the creation of fine architecture”. In their nomination of Argent, David Chipperfield Architects wrote: “In an industry that is constantly under pressure to deliver projects on time and on budget, Argent remains an extremely supportive and stimulating company to work with.” Wow. That endorsement sounds banally like doing one’s job leveraged to the role of architectural messiah.

To understand more about the architectural awards culture, WHAT_architecture researched (okay googled) ‘architectural awards’. The evidence is compelling: 1. At least one architectural award is given out each day of the year. Since google threw up ‘about 39,700,000 results for ‘architecture + award’ perhaps the upper parameter is more like ‘a hundred thousand’ awards each day. This reminds me of my attendance at the Bangladeshi Football Awards in 2014 and so keen were the community that everyone emerge a winner, that there were excess trophies with the compere asking the audience to come forward such that no one shall leave empty handed. 2. There are few gongs handed out for architecture failure. Building Design has the Carbuncle Cup… In Bleak Houses by Timothy J. Brittain-Catlin, the publisher (MiT Press) writes that “the usual history of architecture is a grand narrative of soaring monuments and heroic makers. But it is also a false narrative in many ways, rarely acknowledging the personal failures and disappointments of architects. In Bleak Houses, Timothy Brittain-Catlin investigates the underside of architecture, the stories of losers and unfulfillment often ignored by an architectural criticism that values novelty, fame, and virility over fallibility and rejection. Brittain-Catlin tells us about Cecil Corwin, for example, Frank Lloyd Wright’s friend and professional partner, who was so overwhelmed by Wright’s genius that he had to stop designing; about architects whose surviving buildings are marooned and mutilated; and about others who suffered variously from bad temper, exile, lack of talent, lack of documentation, the wrong friends, or being out of fashion. As architectural criticism promotes increasingly narrow values, dismissing certain styles wholesale and subjecting buildings to a Victorian litmus test of “real” versus “fake,” Brittain-Catlin explains the effect that this superficial criticality has had not only on architectural discourse but on the quality of buildings. The fact that most buildings receive no critical scrutiny at all has resulted in vast stretches of ugly modern housing and a pervasive public illiteracy about architecture. Architecture critics, Brittain-Catlin suggests, could learn something from novelists about how to write about buildings. Alan Hollinghurst in The Stranger’s Child, for example, and Elizabeth Bowen in Eva Trout vividly evoke memorable houses. Thinking like novelists, critics would see what architectural losers offer: episodic, sentimental ways of looking at buildings that relate to our own experience, lessons learned from bad examples that could make buildings better.”

Tim Britt Catlin talks Failure

179prs_LETS PLAY: THE ARCHITECT

According to Wikipedia, a Let’s Play is “a video, or less commonly a series of screenshots, documenting a playthrough of a video game, always including commentary by the gamer. A Let’s Play differs from a walkthrough or strategy guide by focusing on an individual’s subjective experience with the game, often with humorous, irreverent, or critical commentary from the gamer, rather than being an objective source of information on how to progress through the game.” “From the onset of computer video entertainment, video game players with access to screenshot capture software, video capture devices, and screen recording software have recorded themselves playing through games, often as part of walkthroughs, speedruns or other entertainment form. One such form these took was the addition of running commentary, typically humorous in nature, along with the screenshots or videos; video-based playthroughs would typically be presented without significant editing to maintain the raw response the players had to the game. Though others, such as The Yogscast, had used the same approach at the time, the forums at the website Something Awful are credited with coming up with the term “Let’s Play” in 2007 to describe such play throughs.” The Yogscast is a network of YouTube broadcasters who produce gaming-related video content, focused around their main YouTube channel, “YOGSCAST Lewis & Simon“. The channel initially gained popularity with its videos about the MMO World of Warcraft though videos about the Minecraft brought it to widespread attention. After receiving help from many sources, some of these now friends wanted help from Brindley and his partner Simon Lane to create YouTube channels of their own. After this point, many more content creators/YouTube channels joined the Yogscast, hence them being known as “The Yogscast Family”. In June 2012, The Yogscast’s primary channel, YOGSCAST Lewis & Simon, became the first channel in the United Kingdom to reach one billion views. By the end of 2014, The Yogscast had:

- 18 members of staff, working ‘behind the scenes’ (not necessarily content creators)

- 19 officially noted networked channels (not all being advertised with The Yogscast’s in-house advertising style)

- A total of 20,867,994 subscribers on YouTube within the noted network

- A total of 5,186,510,091 video views on YouTube within the noted network

179prs_THE NAME GAME

It is… possible to conceive of a science which studies the role of signs as part of social life. It would form part of social psychology, and hence of general psychology. We shall call it semiology (from the Greek semeîon, ‘sign’). It would investigate the nature of signs and the laws governing them. Since it does not yet exist, one cannot say for certain that it will exist. But it has a right to exist, a place ready for it in advance. Linguistics is only one branch of this general science. The laws which semiology will discover will be laws applicable in linguistics, and linguistics will thus be assigned to a clearly defined place in the field of human knowledge.

—Cited in Chandler’s “Semiotics for Beginners”, Introduction.

“The Name Game” is an American pop song written and performed by Shirley Ellis as a rhyming game that creates variations on a person’s name. Ellis told Melody Maker magazine that the song was based on a game she played as a child. The Name Game could also be applied to buildings. Architecture & Design looked at buildings which have had a moniker assigned to them. In 1st place is a building from… NZ! “The Beehive is the common name for the Executive Wing of New Zealand’s parliament buildings. The original concept was designed by Scottish architect Basil Spence in 1964. It got its name due to looking like a beehive.” Duh! Building nicknames are always visual associations. In 2nd place is “The Gherkin or 30 St Mary Axe in London was previously known as the Swiss Re Building. It was designed by Norman Foster and Arup, and was completed in 2003. It got its name due to its highly unorthodox… (da-rah) appearance.” In 5th place is “The Shard: This 87-storey skyscraper is known as The Shard, but also the Shard of Glass, Shard London Bridge and formerly London Bridge Tower. It is currently the tallest building in the European Union and was designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano. Piano’s design was met with criticism from English Heritage, which claimed the building would be “a shard of glass through the heart of historic London”, thus its name was born. It helps it also looks like a shard of glass.” Interestingly enough, NZ has some heritage in nicknames and thus has tiny URLs embedded in its national psyche. Recent commentary during the World Cup Cricket has made colloquial reference to Wellington’s Regional Stadium: “The highlight of Guptill’s late-innings assault was a 110m six he launched over mid-wicket and onto the roof of the ‘Cake Tin’. Beyond architecture, other forms of popular culture have also demonstrated the Name Game. A Dog’s Show was a television series that was screened at prime time on a Sunday night. This gave a mass national audience exposure to ‘canine name games’, Ted, Red, Fred, which facilitate expedient sheep herding!

179prs_GAME OF ARCHITECTURE

[ARCHITECTS] are so desperate to win [COMMISSIONS] they will try “every trick in the book”, says Liverpool captain Steven Gerrard. “I think it’s normal when you play games at that level,” said Gerrard.

179prs_YOU’VE GOT TO BE IN TO WIN: BUT IS IT WORTH IT?

In order to win, or succeed at something, one must first compete or try. However is the pain worth the gain? When considering entering an architectural competition one must surely ask: “is it worth the effort?“

According to Wonderland: „Architects invest more than 5,000 hours of work per year averaging ten competition entries per annum. However, at best, only one of those projects is getting realised. The reliability in the competition system exists nonetheless: for 40 percent of all participating architects’ offices in this exhibition, competitions are the principal source of income.“ Really? A principal source of income? What country are they talking about? Hmmm… time to do some practice-based research. Nonetheless, at the Galerie architektury the exhibition „Deadline Today!“ will be shown until April 22nd 2015. It is based upon a Wonderland study, a call for individual experiences with competition practices – displayed in stories, ideas and photos – that went out to over 100 European architectural teams.