Gossip as discourse.

Whilst studying under Peter Cook of #Archigram at @TheBartlett in the mid-nineties I was exposed to architectural discourse as tittle-tattle. Yet as this article in @TheObserver suggests, gossip unlocks the secrets of power: or rather what I experienced as an exposure to the back story of architectural politics.

179prs_STRATEGY: THE UNDERCUT

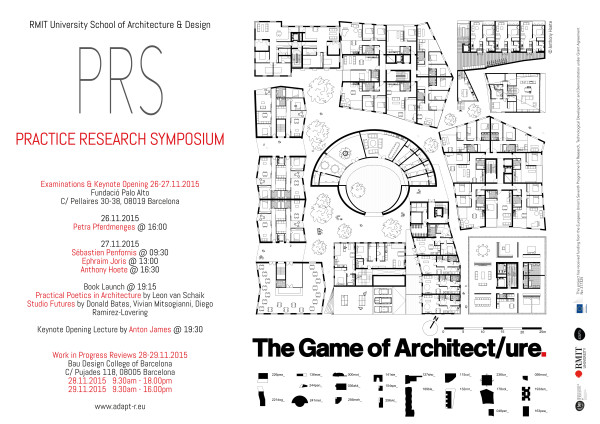

The Game of Architecture asks what could architectural practice learn from, games1? What could, for example, architecture learn from something as seemingly remote as the sport of Formula 1? Having watched the climax to the F1 season which is the Abu Dhabi 2016 GP, I pondered whether:

- the reigning Champion Hamilton Lewis was actually performing “dirty tricks”, as another driver Sebastian Vettel later alleged, or was Hamilton merely undertaking professional gamesmanship strategies that even most viewers understood before the race (meaning it was neither dirty nor a trick)?

- the strategy having not worked however wasn’t the disappointment: Hamilton’s lack of chivalry in defeat mean he came of looking like twice the loser.

179prs_10,000 HOURS ARCHITECTURAL COURSE

There are sooo many awards today that the value of a design award can be measured in seconds. In the preface to a recent award ‘The Power of Now’ by Eckhart Tolle was cited as it supposedly legitimises the idea that true liberation is only be found by living in the instant, in the now! By living in the present only, the past and future cease to exist: atopic architecture doesn’t require any understanding of historic context. There’s no ‘know’ in ‘now’: without previous experience, the ‘now’ becomes the endless pursuit of the ‘new’. Architecture Today, ‘Towards a Now Architecture’ etc etc. The need for speed has been overtaken by the ‘need for now’ yet ‘nowness’ jars with the concept of repetition, of labour, of ‘practice makes perfect’.

In The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance, Anders Ericsson, introduced the concept of ‘10,000-hours’. The paper highlighted the work of a group of psychologists in Berlin, who had studied the practice habits of violin students in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. All had begun playing at roughly five years of age with similar practice times. However, at age eight, practice times began to diverge. By age 20, the elite performers had averaged more than 10,000 hours of practice each, while the less able performers had only done 4,000 hours of practice. The psychologists didn’t see any naturally gifted performers emerge and this surprised them. If natural talent had played a role it wouldn’t have been unreasonable to expect gifted performers to emerge after, say, 5,000 hours. Anders Ericsson concluded that “many characteristics once believed to reflect innate talent are actually the result of intense practice extended for a minimum of 10 years”. The 10,000 hours rule-of-thumb could be the guide for the length of study for an architect as 10,000 hours equals 1,250 days or approximately 5 years of study.

Image taken from Wonderland’s Manual for Emerging Architects. Whilst Europe has disparate minimum study periods for an architecture, by using hours rather than years students could responsively adjust learning speed.

Image taken from Wonderland’s Manual for Emerging Architects. Whilst Europe has disparate minimum study periods for an architecture, by using hours rather than years students could responsively adjust learning speed.

Image taken from Wonderland’s Manual for Emerging Architects. Whilst Europe has disparate minimum study periods for an architecture, by using hours rather than years students could responsively adjust learning speed.

Image taken from Wonderland’s Manual for Emerging Architects. Whilst Europe has disparate minimum study periods for an architecture, by using hours rather than years students could responsively adjust learning speed.

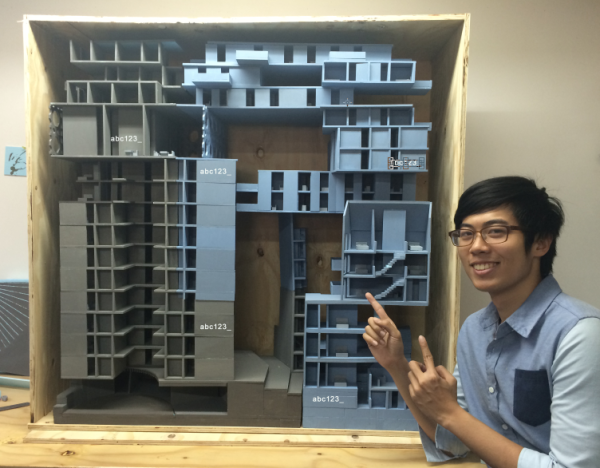

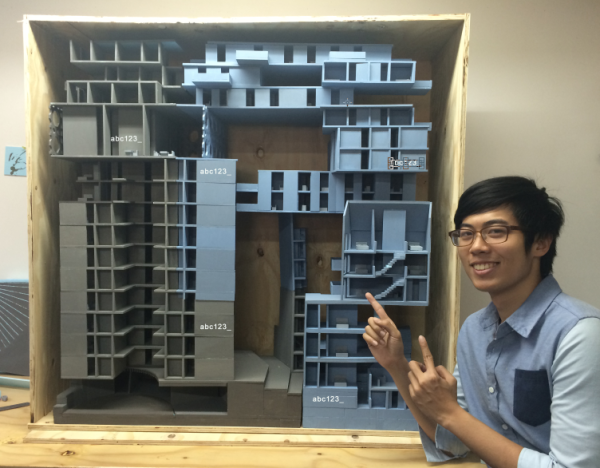

179prs_rubicon model as elevator musak

The making the Game of Housing rubicon model required a certain amount of last minute improvisation. Innovation begs for greater spontaneous performativity. Design deadline stresses produce the live clarity of ‘making it up as you go along’. If architecture is really frozen music, then it would appear to lack this spontaneity. Yet the first time film was scored to jazz it produced the ‘Elevator Musak’ of Miles Davis improvising to Louis Malle’s Ascenseur pour l’Echafaud (Elevator to the Gallows). The rest is history…

179prs_annotate!

Make sure the Rubicon is fully annotated! Add project numbers…

Game of Housing: rubicon model

179prs_PRS BOX

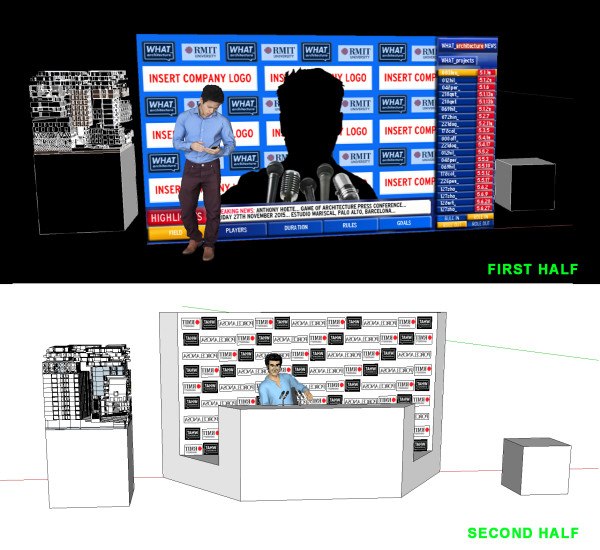

In case you forgot, PRS is the RMiT’s ‘Practice-Research Symposium’: a longstanding programme of research into what venturous designers actually do when they design. ‘PRS Box’ is the Game of Architecture’s take on the designer presentation through the use of a press box. Recognising that the presentation is an equip-mix of monologue and dialogue (45 minutes each way), the first half shows the PRS box configured for a standing presentation. At halftime, the PRS Box is rotated 180 degrees to transform into a seated dialogue Q&A session for the second half.

Wikipedia nearly says this say about the architecture of the Press Box: The press box is a special section of an arena set up for the media to report about a given event. In general, critics sit in this box and write about the on-field event as it unfolds. The press box is considered to be a production space. As such, cheering is strictly forbidden in press boxes, and anyone violating rules against showing favouritism can be subject to ejection.

In case you forgot, PRS is the RMiT’s ‘Practice-Research Symposium’: a longstanding programme of research into what venturous designers actually do when they design. ‘PRS Box’ is the Game of Architecture’s take on the designer presentation through the use of a press box. Recognising that the presentation is an equip-mix of monologue and dialogue (45 minutes each way), the first half shows the PRS box configured for a standing presentation. At halftime, the PRS Box is rotated 180 degrees to transform into a seated dialogue Q&A session for the second half.

Wikipedia nearly says this say about the architecture of the Press Box: The press box is a special section of an arena set up for the media to report about a given event. In general, critics sit in this box and write about the on-field event as it unfolds. The press box is considered to be a production space. As such, cheering is strictly forbidden in press boxes, and anyone violating rules against showing favouritism can be subject to ejection.The Game of Architecture is presented via a Press Box.