000off_JACQUES HERZOG TALKS FOOTBALL WITH Ah!

Anthony Hoete and Jacques Herzog talk football versus architecture at the RIBA on 21 April 2007:

Ah!: “I am interviewing you on behalf of www.kultureflash.net, which is a weekly web-based newspaper covering contemporary culture in and around London. In preparing for this interview I decided to undertake some research on your office and, as is the case these days, such research startsarchive at your front door, with your website portal. This research however went out the window when I surprisingly learnt that there is no Herzog and De Meuron website…”

JH: “That is correct. We do not have a website.”

Ah!; “I find that surprising given your global visibility, or perhaps it is because of this, you have no need for web-based public relations: does Google act as proxy for the absent Herzog de Meuron homepage – when I googled <Herzog de Meuron> 604,000 results came up?”

JH: “The function of a website as I see it is purely as archive – a potentially efficient informational store.”

Ah!: “This suggests that you see the architectural website as a retrospective space only…”

JH: “Yes, with 604,000 results there is a necessity to edit and curate information not directly generated within our own architectural practice yet about our architectural practice. Or the buildings at least. Like a mirror, this plethora of information re-presents an image of ourselves as fabricated by others. Herzog De Meuron as written about and pressed into existence by the community of practice. Why should I do my own press, catalogue the practice when you are doing it for me? Is this auto-creation? Google is my editor.

Ah! “In the same way as a building could be created via the perspective of its users? Let’s discuss then one supporter’s story – a ‘fanecdote’ let’s say – regarding the Allianz Arena: how do you react to claims by the ‘ultras’ of Bayern Munich that the stadium is, ironically, too good? The Ultras protested at several home games against the seats and some of the rules of the arena, which they perceive as “fan unfriendly”. For example, a spectator may not enter with a megaphone or a pennant that a single person cannot carry unfurled, and pennant poles with a length of over one metre are prohibited. The complaint is that these rules and the designer seats put a damper on the fan experience.”

JH: “The architect cannot entirely control how a building is used: certain conditions have been imposed that were influenced by the political culture of sports-fan ‘hooliganism’. German football hooliganism started at about the same time as the English phenomenon but has never become as widespread as in England, although German fans severely injured a French police officer during rioting at the World Cup in France 1998. German authorities have often been accused of trying to down play incidents of football related violence. In recent years, acts of hooliganism have been concentrated among supporters of eastern German football clubs and lower league or amateur clubs around the country. German authorities have now reduced its prevalence with tougher laws. Recall now then that two local rivals share the Allianz Arena – FC Bayern München and TSV 1860 München. Oppositional-shared territory would be unheard of here in London: current neighbours Arsenal and Tottenham occupying the same ground – unthinkable! Yet these large urban spaces that were designed to cater for mass audiences remain vacant every other away game week. It is more efficient to maximise occupancy, to have a home game every week. This paradoxically reduces the size of each team’s capital investment yet doubles the design potential…”

Ah! “…as with the Allianz, which specifically uses the footballing tension born from ‘local opposition’ to illuminating effect: the stadium glows with the colors of the respective home team (switching between red for Bayern and blue for 1860– or white if the German national team is playing).

JH “Effects, lights, top players are all part of football drama where we as architects provide the appropriate stage and scenery. For the Allianz Arena we turned to traditional English football stadiums for inspiration, where the fans are as close as possible to the pitch. At Arsenal’s former ground, Highbury, front row fans sat just 1m from the touchline.”

Ah! “The space of English football architecture was historically formed from the compact assemblage of charming ad-hoc grandstands. In the wake of the Hillsborough tragedy in Sheffield in 1989 where 96 Liverpool fans died, yesterday’s grand standing upon the terraces has been converted into today’s all-seater stadiums with the removal of barriers between spectator and performer. However the geometry of the contemporary stadium is such that the seats are much further from the touchline than with the historic grandstand. This increased ‘remoteness’ has coincided with a shift in the drama from events on the field to events in the stadium. The crowds are the new players generating mass participation with song and dance – the so-called Mexican wave, for example, gained international prominence during the 1986 World Cup. At the last world cup in Germany, television cameras frequently focused on celebrity faces in the crowd: the English WAGs (‘wives and girlfriends) providing more stimulus than the underperforming team.”

JH: The audience creates the football stadium not just the architecture. Ever seen a game played behind closed doors? Architecture has to be a sensual intelligent medium; otherwise it’s just boring…

Ah!: An empty stadium would kill televised football. Given the huge income generated by TV rights one can expect television to taking an increasingly significant role in the design of future stadia. Where fans attend for free (or are paid) to enhance the televised drama. Might we envisage tomorrow’s ‘cone of vision stadium’ with the stadium designed around camera angles and the televised image…

JH: Water anyone? (His Press Officer is sitting next to him).

Ah!: Thanks. Architecture like football also requires strategies and high levels of organisation…

JH: Yes the organisation of urban infrastructure has to intersect with mass sporting attendances: the 69,000 seat Allianz Arena sits over Europe’s largest parking structure, comprising four 4-story deep parking garages with nearly 10,000 parking places. Ideally, architecture changes a city.

Ah!: That’s approx 1 parking place for every 7 persons. At the recently open Wembley there is no general public parking at the new stadium. There is also no need for such an under-utilised ‘national stadium’ in Germany, Italy or Spain where national teams play their home games around the country maximizing their exposure to varying localised audiences. Football is very ‘terror-torialised’ here in the UK. Do you still play?

JH: Yes, I admire total football. The constant switching of positions of Total Football only came about because of enhanced spatial awareness. It was about making space, coming into space, and organising space-like architecture on the football pitch. The system developed organically and collaboratively… democratic too: everyone could play everywhere! A player who moves out of his position is replaced by another from his team thus retaining their intended organisational structure. In this fluid system no footballer is fixed in his or her intended outfield role; anyone can be successively an attacker, a midfielder and a defender.

Ah!: The Dutch, who developed Total Football, also forged a reputation for modernising architecture by recognising that the increasing complexity of the city demands a reverse simplification of architecture. This is confirmed in the iconic status of today’s contemporary architecture. Learning from maestro Johan Cryuff who as a winger played at the edges of the field, simple football/architecture results in the most beautiful game yet producing simple football/architecture however is a difficult thing…

JH: Sometimes it’s not about winning but how you play the game…

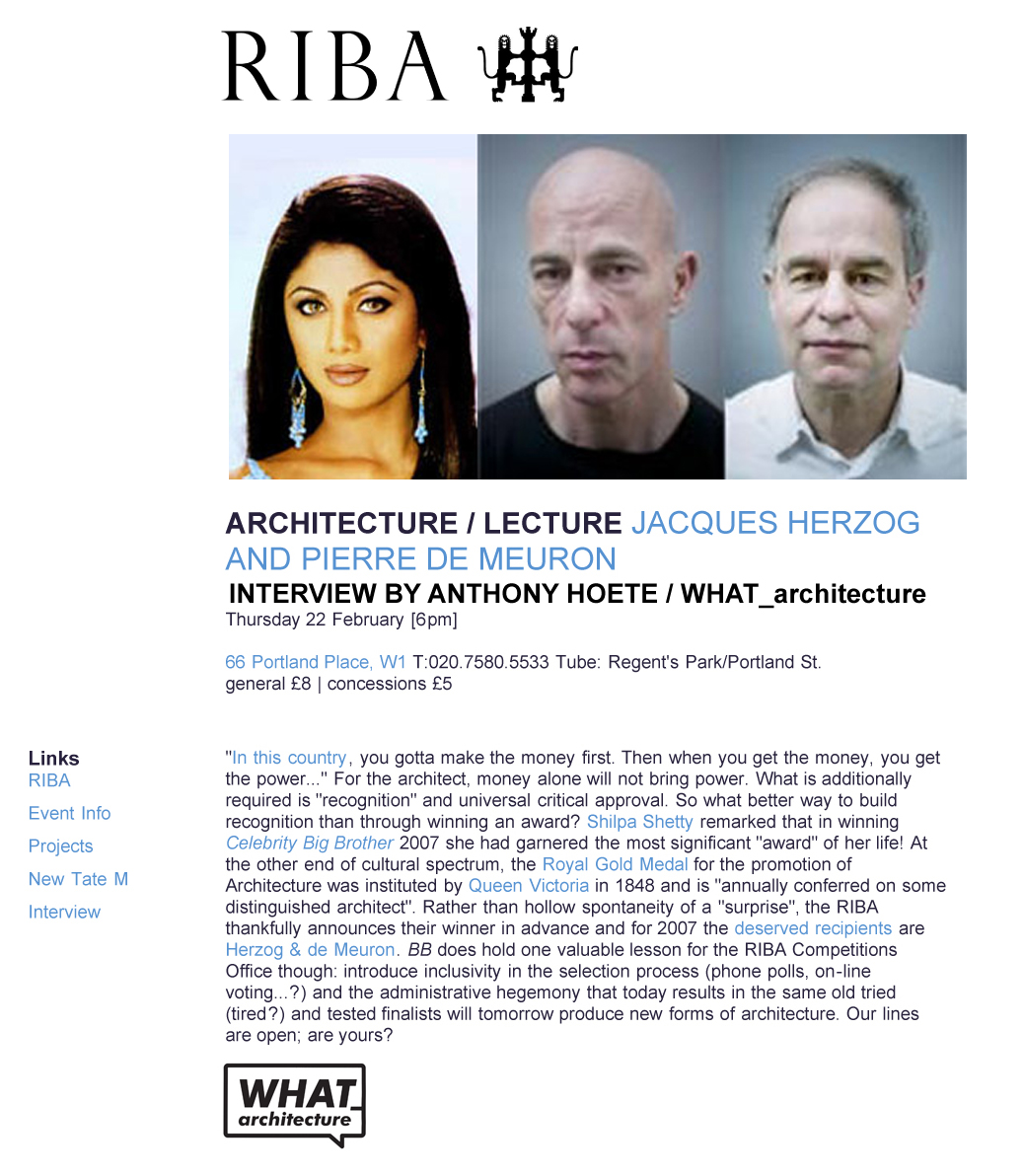

Ah!: Yes although architecture shares with football a trophy culture with competitions, awards and medals. It is thus apt to close this discussion with a reflection on your own winner’s medal. The 2007 RIBA Gold Medal is going to an architectural duo for only the 3rd time since its inception in 1848. However in the previous instances – Charles and Ray Eames in 1979 and Michael and Patty Hopkins in 1994 – these were husband and wife couples and so for the first time we have a winning team and with this the recognition of architecture as a collaborative process….

JH: (too embarrassed to answer…)

———— RIBA FOOTNOTES ————-

Herzog & de Meuron Architekten is a Swiss architecture firm, founded and headquartered in Basel, Switzerland in 1978. The careers of founders and senior partners Jacques Herzog (1950), and Pierre de Meuron (1950), closely parallel one another, with both attending the ETH in Zürich. In 2006, the New York Times Magazine called them “one of the most admired architecture firms in the world.”

HdeM’s early works were reductivist pieces of modernity that registered on the same level as the minimalist art of Donald Judd. However, their recent work at Prada Tokyo, the Barcelona Forum Building and the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Olympic Games, suggest a changing attitude. Though their commitment to the primacy of materiality shows through all their projects, the manipulation of form has gone from boxy modernism to volumetric prisms of equal if not greater presence. The architects often cite Joseph Beuys as an enduring artistic inspiration and collaborate with different artists on each architectural project. Their success can be attributed to their skills in revealing unfamiliar or unknown relationships through familiar materials.

Anthony Hoete is a partner in the office WHAT_architecture that recently won a 2006 Regeneration Award for its Rooftop Nursery. Hoete is also the Editor of the spatial mobility book ROAM (BDP 2003) which Peter Wilson declared in his Building Design review declared “deviant, frustrating yet crucial…” Next up? WHAT_architecture is currently collaborating with AKK Architectes on the ‘Moroccan roll’ House Beirutiful soon to be completed in West London.

SAY WHAT_!?