Pepeha as map: the indigenisation of architecture school.

A pepeha is a different way of introducing one’s self. More personal than a business card, more bee’s knees than a personal greeting whereby one simply offers a name – which is then forgotten.

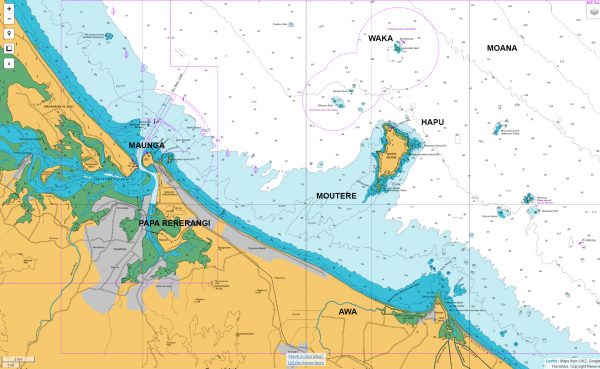

A pepeha offers all NZers, not just Māori, a way of learning about one’s sense of place. A pepeha connects you to your landscape as taonga: to maunga, awa and moana. In doing so we learn more about the (his)stories of Aoteroa and thus all NZers can participate in the embrace of Māori culture. No matter where in the world you are or are from, a pepeha allows one to enter a Te Ao Māori and to find your mountain, your river, your sea, your boat, your land. You source your own personal wairua, your own personal mauri, your own mana whenua from those places you consider home. A pepeha is a map of your personal landmarks and these landmarks are your people.

Ko Mataatua me Queen Mary ngā waka

Ko Toitehuatahi toku-Moana

Ko Mauao te maunga

Ko Kaituna toku awa

Ko Mōtītī toku motuere

Ko Tauranga te papa rererangi

Ko Ngāti Awa me Ngāti Ranana ngā iwi

Ko Patuwai toku hapu

Ko Stichtingbureau de architectenregister de Nederlands me Royal Institute of British Architects me Te KāhuiWhaihanga ngā whare takuira

Ko WHAT_architecture te pakihi

Ko Aubrey tōku mātua

Ko Māui Pehiamuopatuwai tōku tama

Ko Anthony Hoete tōku ingoa

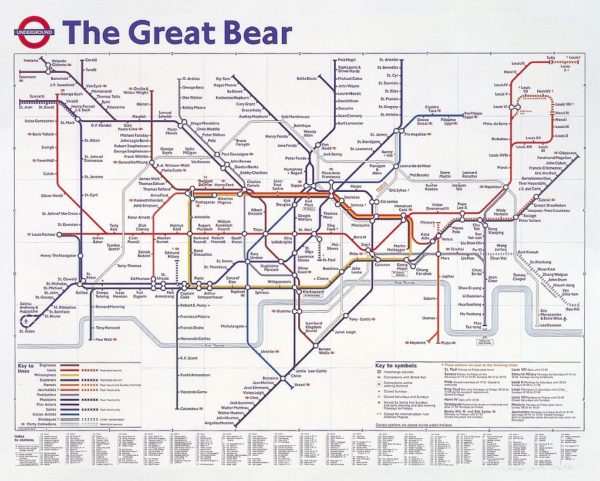

The Great Bear by Simon Patterson (1992) reworks the already brilliant London Tube map in an entertaining way but through minimal means. Patterson didn’t change the map’s overall appearance (the lines’ colours remain the same, the circle icons representing stations are intact and the fonts are all unchanged); what he does, on closer inspection, is to simply change the stations’ names and assign roles to the lines.

The Northern line thus represents ‘Actors’, the Central line ‘World Leaders’ whilst the Overground line ‘Comedians’. Tottenham Court Road is now ‘Gina Lollobrigida’; Camden Town ‘Peter Fonda’; Stratford ‘Napoleon’ and Brondesbury Park ‘Spike Milligan’. When different Tube lines intersect their roles overlap. So West Hampstead, where the Jubilee line (‘Footballers’) meets the Overground line (‘Comedians’) meet becomes ‘Paul Gascoigne’ – after the 1990s baffooning footballer.

As with any artwork, though, there’s something more profound at work with The Great Bear than mere amusement. By not just retaining the look and iconography but the exact detail of the Tube map, yet substituting the expected and often familiar station names for names of well-known figures from completely different realms of our experience, it creates a slightly jarring, even confusing effect. Although this effect may only be there for a few seconds until we figure out what’s going on and it becomes funny, it’s long enough to lodge in the brain and, thus, cleverly demonstrates how the everyday and the expected can be subverted.

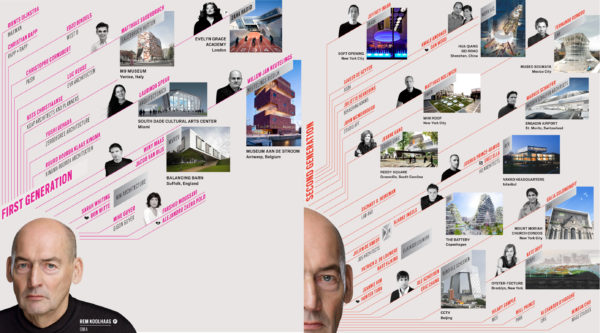

Form Follows Whakapapa: a tikanga Māori for tracing architectural influence.

Whakapapa means genealogy and is the core of traditional mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). If we apply this Māori concept of tracing genealogy to architecture, then we have a genealogical framework for tracing architectural influence in Aotearoa. If we accept Form Follows Whakapapa we can then start to navigate the future of the built environment.

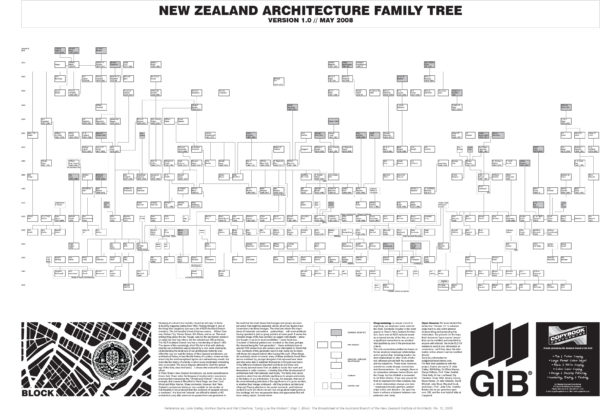

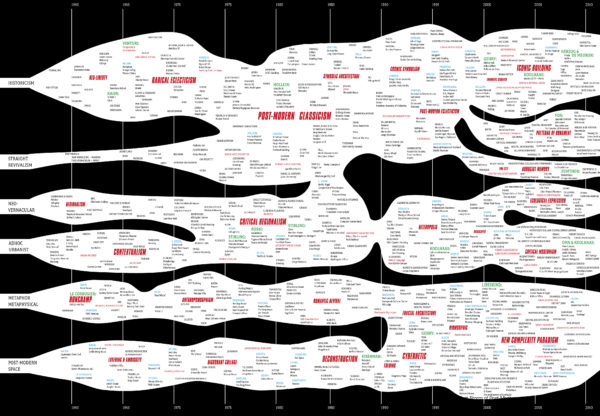

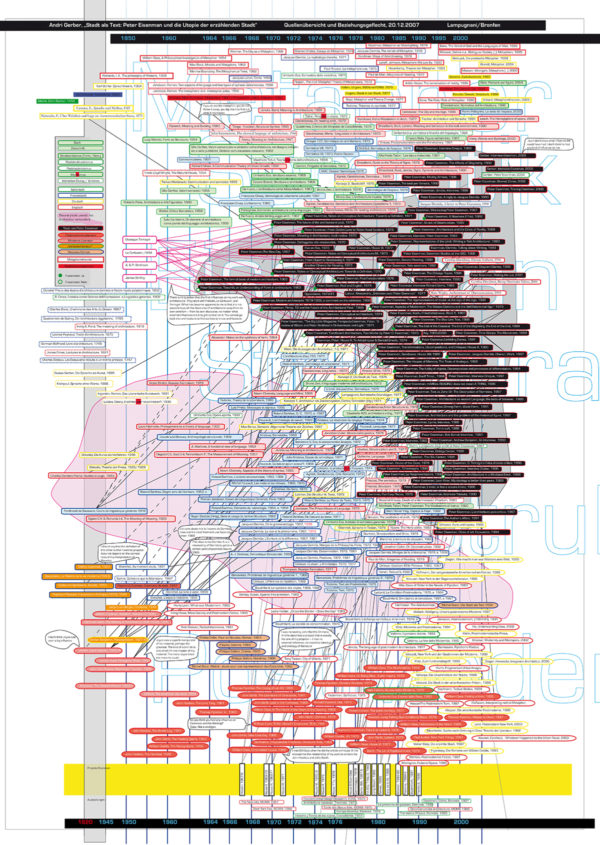

Form Follows Whakapapa binds our architectural relationships so that ideology, mythology, history, knowledge and custom are organized, preserved and transmitted from one generation to the next. Drawing and modeling avows a particular spatial knowledge such that the architect is well versed in infographics and diagrams. Whilst it might be tempting to consider information visualization a relatively new field that rose in response to the demands of the Internet generation, “as with any domain of knowledge, visualizing is built on a prolonged succession of efforts and events.”[1] In tracing architectural influence, it is likely that the family tree diagram will need to accommodate the efforts and events of: architects (Andrew Barrie’s NZ Architecture Family Tree, OMA Family Tree), ideologies (Charles Jenck’s Evolutionary Tree), publications (Andri Gerber’s Meta History tree) and even projects!? After all, every project the architect undertakes will ‘reference’ other projects, with branches according to: scale, materiality, landscaping.

Māori whakapapa and Foucault’s genealogy as methods of organising information… TBC

See also Barnaby Bennett’s excellent: Whakapapa and Architecture. Peer, Glimpse and Gaze: a pakeha view.

- Lima, Manuel The Book of Trees: Visualizing Branches of Knowledge

# THE FUNAMBULIST PAPERS 40 /// META-HISTORY, OR HOW TO TEACH HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE IN THE ERA OF NEW MEDIA BY ANDRI GERBER

MTV Te Ao Tapatahi: decolonising the curriculum

In this beautiful and transformative book, 24 Māori academics share their personal journeys, revealing what being Māori has meant for them in their work. Their perspectives provide insight for all New Zealanders into how mātauranga is positively influencing the Westerndominated disciplines of knowledge in the research sector. It is a shameful fact, says co-editor Jacinta Ruru in her introduction to Ngā Kete Mātauranga, that in 2020, only about 5 percent of academic staff at universities in Aotearoa New Zealand are Māori. Tertiary institutions have for the most part been hostile places for Indigenous students and staff, and this book is an important call for action. ‘It is well past time that our country seriously commits to decolonising the tertiary workforce, curriculum and research agenda,’ writes Professor Ruru. The book demonstrates the power, energy and diversity that can be brought out into the world by Māori scholars working both comfortably and uncomfortably from within, without and across diverse academic disciplines and mātauranga Māori. – Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith These deeply personal stories provide a portal into the te ao Māori world, which many outside it seek to understand, but struggle to find a frame in which to do so. The abstract concept of decolonising the tertiary workforce is brought to life and given meaning by these kōrero of strength, where the authors display courage and vision from within an environment so often hostile to Indigenous ways of knowing. Read it, be inspired, and welcome this refreshingly written challenge to embrace mātauranga Māori and build a stronger academy. – Professor Juliet A. Gerrard, Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor

MTV: TeAoTapatahi: CLT and the iwi forest