179prs_Cross-reading: architectural theory as mash-up!

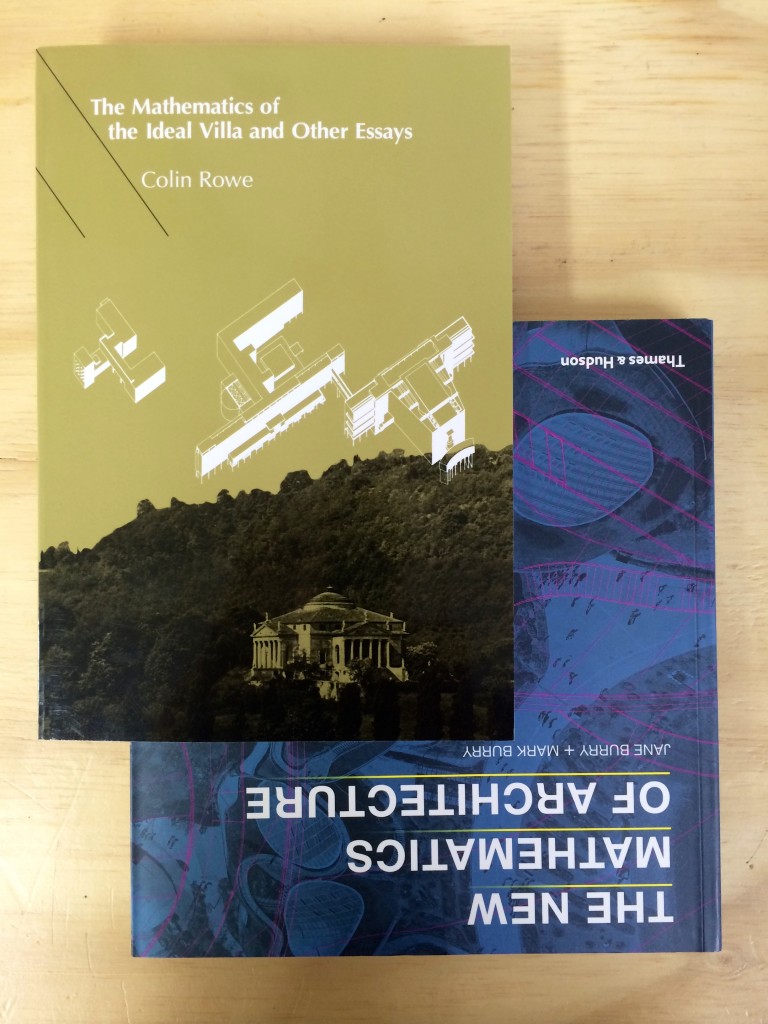

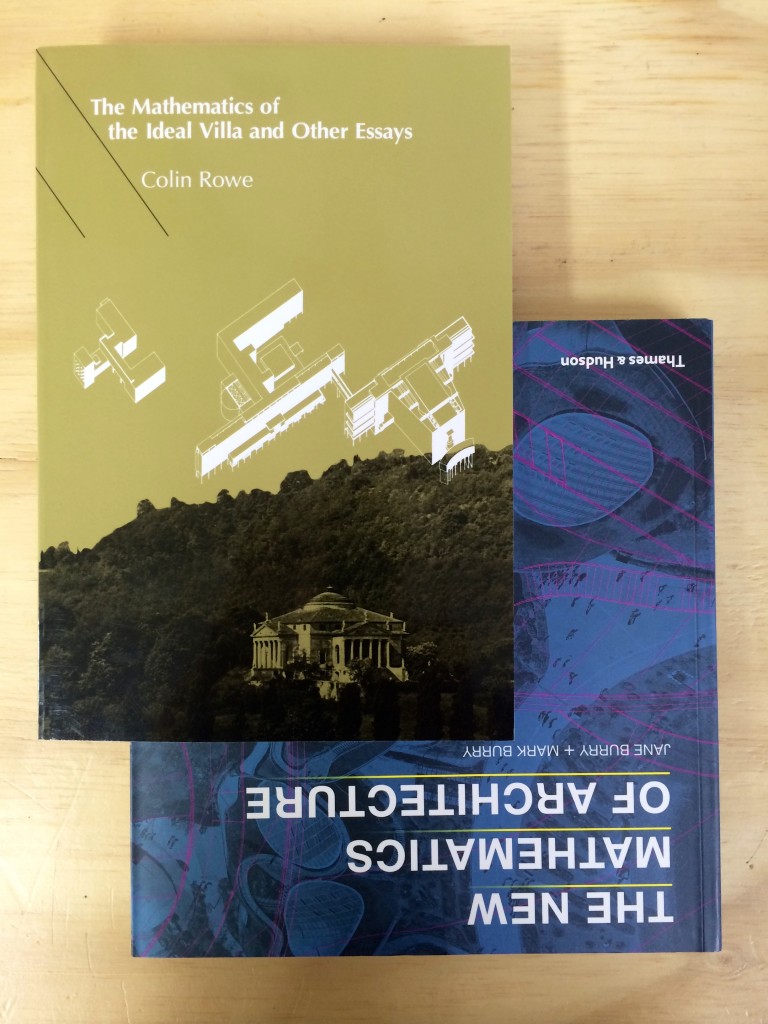

In the same way as Radio Soulwax (2ManyDjs) adeptly mashed two songs seamlessly together, it is not uncommon to read two (or more) books at the same time. If architectural theory accommodated a critical mash-up this would lead to counterpoint and cross-reading! To that end I am currently cross-reading… Colin Rowe’s “The Mathematics of the ideal Villa and Other Essays” from 1947 (which compares the design of geometric proportioning in the work of Palladio and Le Corbusier) with Mark and Jane Burry’s The New Mathematics of Architecture from 2010 (which observes digital design in architectural morphology). What does this mash-up cross-reading avow? In a sentence: a mathematical shift from abstract volumetrics to complex surfaces.

237dog_THE CANOPHILIST’s FIRST FINE DINING FOR DOGS

A holistic restaurant for four-legged friends, The Curious Canine Kitchen will pop up on Saturday 11 & Sunday 12 April in, da-rah, Shoreditch. Featuring two seating’s each day (1-3pm & 3-5pm) this ‘Doggie Fine Diner’ is the first of its kind in Britain to serve high-end, freshly prepared, organic canine cuisine. Lucky Foodie Fido’s will be treated to a five-course, drink paired set menu. Items on the “The Nature Way Tasting Menu” for dogs include Textures of Tripe with seaweed and kale puree, crispy Paddywack with reishi mushroom flaxseed cream and coconut and blueberry chia pudding with gluten-free cinnamon quinoa ‘dog biscuits’ to name a few. Served alongside refreshments such as Alkaline water, beef consommé and coconut water, the menu will be polished off with a piquant marrowbone, known for its teeth cleaning properties and a ‘Fresh Breath’ herbal tea tonic to aid digestion. Served by waiters at one of the restaurants four bespoke doggy tables, any left over’s will be available to take home in a doggy bag, along with a special goody bag featuring some easy tips and tricks on introducing fresh foods and herbs to a dogs diet as well as recipes and samples from dog loving sponsors including brands such as Diet D’Og and Woof&Brew. On-site entertainment includes a fido photo booth for posing pooches. Not wishing dog owners to miss out on the action.. they too will be served an assortment of seven, raw whole food amuse-bouche and a variety of drinks as part of a set ‘Rawsome Tasting Menu’. Featuring a range of the superfoods presented in the doggie menu including spirulina, flaxseed, coconut oil and chia, the menu which includes items such as gazpacho raw soup, golden quinoa, coconut and mango salad as well as avocado, blueberry and chia cheesecake demonstrates how culinary ingredients can be shared between owners and their hounds.

http://www.curiouscaninekitchen.com

The image below compares breakfasts: my son’s breakfast (left) vs our dog’s (right).

A holistic restaurant for four-legged friends, The Curious Canine Kitchen will pop up on Saturday 11 & Sunday 12 April in, da-rah, Shoreditch. Featuring two seating’s each day (1-3pm & 3-5pm) this ‘Doggie Fine Diner’ is the first of its kind in Britain to serve high-end, freshly prepared, organic canine cuisine. Lucky Foodie Fido’s will be treated to a five-course, drink paired set menu. Items on the “The Nature Way Tasting Menu” for dogs include Textures of Tripe with seaweed and kale puree, crispy Paddywack with reishi mushroom flaxseed cream and coconut and blueberry chia pudding with gluten-free cinnamon quinoa ‘dog biscuits’ to name a few. Served alongside refreshments such as Alkaline water, beef consommé and coconut water, the menu will be polished off with a piquant marrowbone, known for its teeth cleaning properties and a ‘Fresh Breath’ herbal tea tonic to aid digestion. Served by waiters at one of the restaurants four bespoke doggy tables, any left over’s will be available to take home in a doggy bag, along with a special goody bag featuring some easy tips and tricks on introducing fresh foods and herbs to a dogs diet as well as recipes and samples from dog loving sponsors including brands such as Diet D’Og and Woof&Brew. On-site entertainment includes a fido photo booth for posing pooches. Not wishing dog owners to miss out on the action.. they too will be served an assortment of seven, raw whole food amuse-bouche and a variety of drinks as part of a set ‘Rawsome Tasting Menu’. Featuring a range of the superfoods presented in the doggie menu including spirulina, flaxseed, coconut oil and chia, the menu which includes items such as gazpacho raw soup, golden quinoa, coconut and mango salad as well as avocado, blueberry and chia cheesecake demonstrates how culinary ingredients can be shared between owners and their hounds.

http://www.curiouscaninekitchen.com

The image below compares breakfasts: my son’s breakfast (left) vs our dog’s (right).

000off_TIME FOR TEA

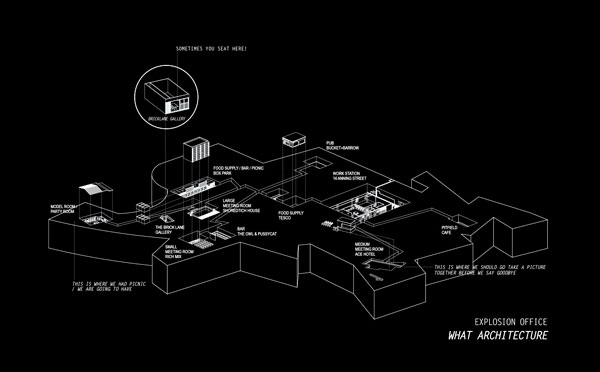

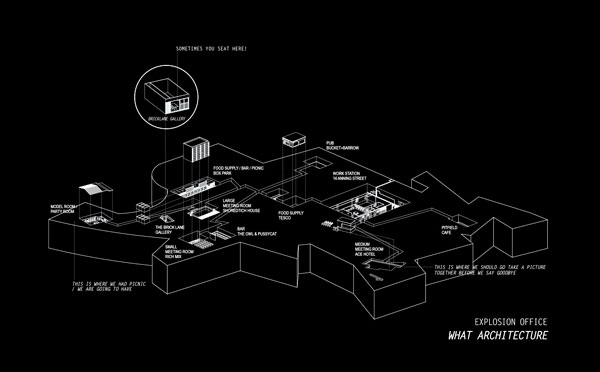

Akin to traditional Tokyo living where many domestic functions were located outside the house (bath house, okonomiyaki kitchens…), the current WHAT_office is an ‘exploded’ office. Exploded in the sense that our three client spaces are located just outside the office. All three ‘Meeting Rooms’ needless to say are dog friendly:

- Meeting Room A: Ace Hotel, 100 Shoreditch High Street;

- Meeting Room F: the Forge and Co. at 154 Shoreditch High Street

- and finally Meeting Room T: at Time For Tea which is cryogenically frozen in time: that is the 1920s. Local resident Dan Cruickshank, the art historian, BBC TV presenter and architectural chronicler reports on Meeting Room T Johnny Vercoutre’s preservation project on Spitalfield’s Life.

179prs_AND THE LOSER IS… IT’S NOT THE WINNING, IT’S THE PLAYING OF THE GAME OF ARCHITECTURE.

We have often asked on blablablarchitecture: if WHAT_architecture awarded an architectural prize what or to whom would it be for? The RIBA has a client Award recognising “the key role that a good client plays in the creation of fine architecture”. In their nomination of Argent, David Chipperfield Architects wrote: “In an industry that is constantly under pressure to deliver projects on time and on budget, Argent remains an extremely supportive and stimulating company to work with.” Wow. That endorsement sounds banally like doing one’s job leveraged to the role of architectural messiah.

To understand more about the architectural awards culture, WHAT_architecture researched (okay googled) ‘architectural awards’. The evidence is compelling: 1. At least one architectural award is given out each day of the year. Since google threw up ‘about 39,700,000 results for ‘architecture + award’ perhaps the upper parameter is more like ‘a hundred thousand’ awards each day. This reminds me of my attendance at the Bangladeshi Football Awards in 2014 and so keen were the community that everyone emerge a winner, that there were excess trophies with the compere asking the audience to come forward such that no one shall leave empty handed. 2. There are few gongs handed out for architecture failure. Building Design has the Carbuncle Cup… In Bleak Houses by Timothy J. Brittain-Catlin, the publisher (MiT Press) writes that “the usual history of architecture is a grand narrative of soaring monuments and heroic makers. But it is also a false narrative in many ways, rarely acknowledging the personal failures and disappointments of architects. In Bleak Houses, Timothy Brittain-Catlin investigates the underside of architecture, the stories of losers and unfulfillment often ignored by an architectural criticism that values novelty, fame, and virility over fallibility and rejection. Brittain-Catlin tells us about Cecil Corwin, for example, Frank Lloyd Wright’s friend and professional partner, who was so overwhelmed by Wright’s genius that he had to stop designing; about architects whose surviving buildings are marooned and mutilated; and about others who suffered variously from bad temper, exile, lack of talent, lack of documentation, the wrong friends, or being out of fashion. As architectural criticism promotes increasingly narrow values, dismissing certain styles wholesale and subjecting buildings to a Victorian litmus test of “real” versus “fake,” Brittain-Catlin explains the effect that this superficial criticality has had not only on architectural discourse but on the quality of buildings. The fact that most buildings receive no critical scrutiny at all has resulted in vast stretches of ugly modern housing and a pervasive public illiteracy about architecture. Architecture critics, Brittain-Catlin suggests, could learn something from novelists about how to write about buildings. Alan Hollinghurst in The Stranger’s Child, for example, and Elizabeth Bowen in Eva Trout vividly evoke memorable houses. Thinking like novelists, critics would see what architectural losers offer: episodic, sentimental ways of looking at buildings that relate to our own experience, lessons learned from bad examples that could make buildings better.”

Tim Britt Catlin talks Failure