000off_WHAT_cucina giuliana

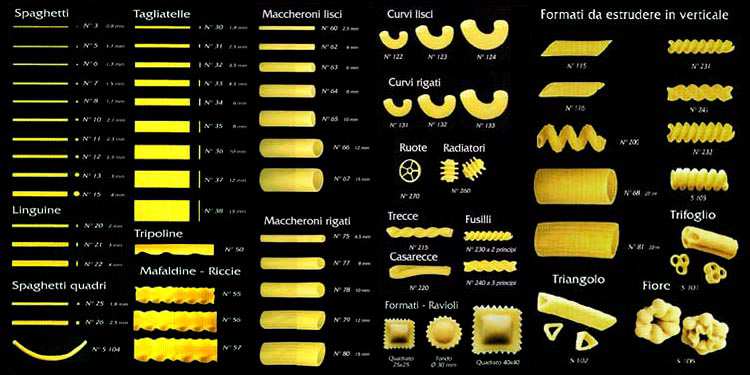

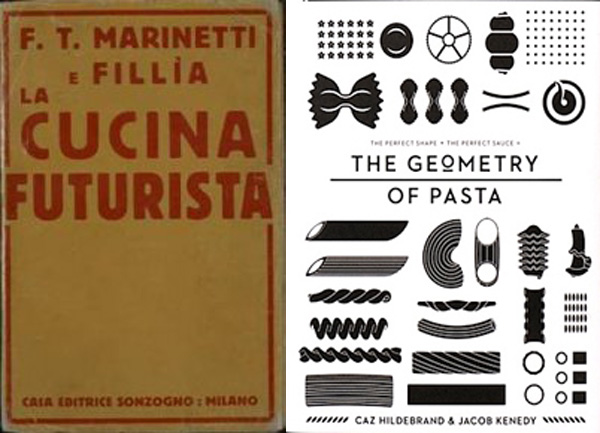

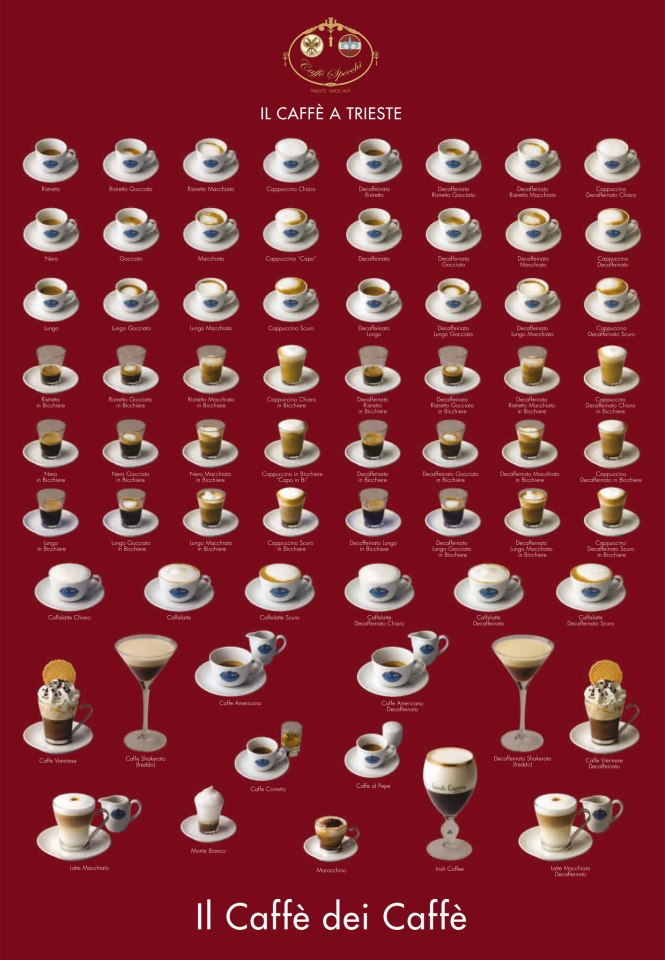

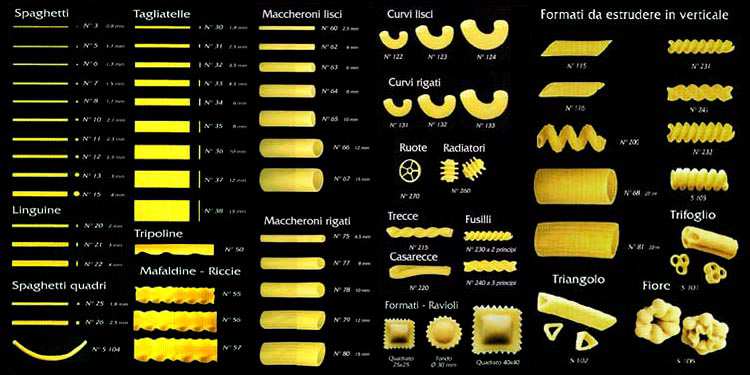

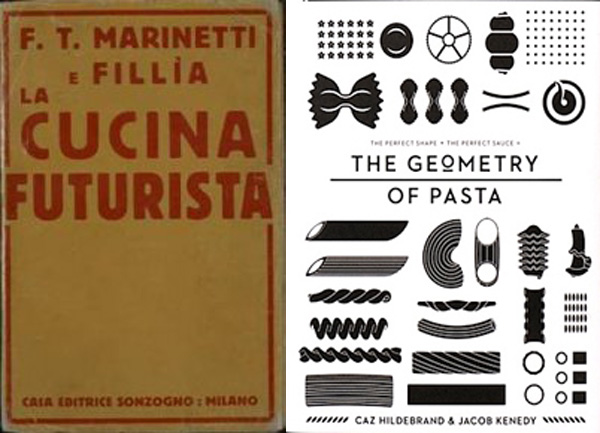

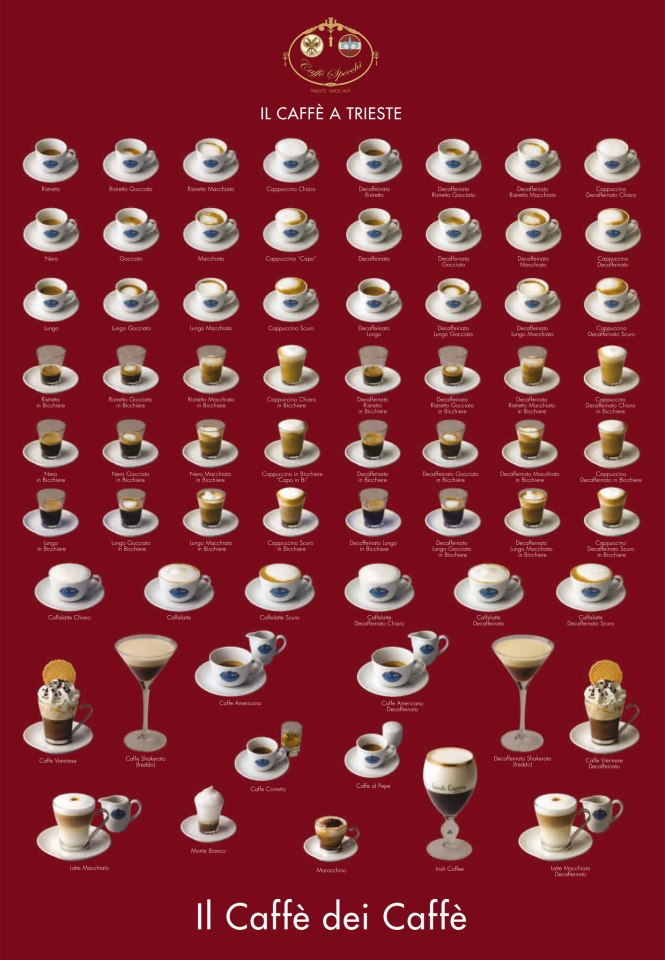

Hailing from Trieste, Giulio Tomasi’s project in the WHAT_office kitchen is a continuation of the Italian modernist culinary legacy which started with the Futurist’s Cookbook and more recently was represented in George Legrende’s The Geometry of Pasta. The multiplicity of the Italian kitchen derives from it’s matrix permutative potential: 500 pasta forms + 100 sauce types = 50,000 buoni appetiti! And of course, after eating, voila: welcome to the digestivo café matrix!

072hin_WHAT NEXT?

Archeological Maintenance at Hinemihi looks suspiciously like architectural dentistry… or getting buildings to talk confidently!

000off_WALLPAPER ARCHITECTURE

Paper Architecture was a term deployed by Soviet art critics to denote fantastical designs could influence the development of architecture. Paper Architecture also derives its traditions from 18th century designs originating in Italy and France. Basically, Paper Architecture is universally under stood as architecture that is not building.

WallPaper Architecture is WHAT_architecture deploying the iconography of Paper Architecture as surface relief. This could range from WHAT_WallPaper as conversational understood as an interior deçor backdrop through to WHAT_WallPaper as an urban interior: paper clad buildings. Paper as an exterior degenerating but therefore always changing and open to reinterpretation.

000off_Ekumenopolis: City Without Limits

Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits.

Ecumenopolis is a word invented in 1967 by the Greek city planner Constantinos Doxiadis to represent the idea that in the future urban areas and megalopolises would eventually fuse and there would be a single continuous worldwide city as a progression from the current urbanization and population growth trends.

The concept of ecumenopolis was first used in Turkey by Ahmet Vefik Alp, a renowned Turkish architect and urban planner, who variously defined Istanbul as a “a nightmare city,” a “cancerous city” and a ‘city on steroids” which has run out of its green spaces, water and other natural resources due to enormous growth.

Ekumenopolis is also a film by Turkish film-maker Imre Azem that details this uncontrolled, money-driven expansion of Istanbul as the city heads towards a population of 15 million people – twice the size of London. It sheds light on current events as prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s police clash violently with protesters outraged by plans to build in a city centre park. Istanbul wants to play in the big leagues. in 2010, it was the European City of Culture. It has its heart set on winning the 2020 Olympic bid. And the government wants it to be the financial centre of the region. Its population looks set to double to 30 million by 2030. But there is every sign that this unchecked growth is coming at a devastating cost. In Ekumenopolis, Azem dissects the reasons Istanbul is groaning under its rapid expansion with a striking aural and visual landscape and by speaking to a wealth of experts and developers. He also follows a group of families forced to live in tents after being chucked out of their homes, to make way for luxury skyscrapers. The lack of planning regulations means that expansion has come without adequate environmental or safety precautions. In fact, an estimated 70% of the city’s 3.8 million buildings are thought to be unsafe — and lying on a fault line. As one interviewee warns, for Istanbul the future means chaos.

132nnr_ONE VOLUME, THREE TENURE PLUG-INS

A singular building volume can accommodate three different development scenarios:

POCKET: 21 micro flats (100% affordable) of: 1b2p

MIXED: 14 flats (50% affordable) of: 8x2b3p + 3 x 3b4p + 3 x 1B2p

PRIVATE: 10 flats of: 3 duplex x 2b3p + 4 x 2b3p + 1 x 3b4p + 1 x 1b2p + 1 penthouse x 2b4p

000off_Casa da Musique concrète

To celebrate the impending opening of the 3rd edition of the Architecture Triennale of Lisbon, WHAT_architecture was commissioned to review one ‘Portuguese building’. So we chose the happy accident of an office Portu-Polish wedding to ‘revisit’ OMA’s Casa da Música in Porto nearly one decade after its completion. What follows is not the completed review (which is ‘saved’ for the Triennale opening on the 12th September 2013) but merely a question triggered by a first sight: does contemporary architecture have to be shiny and new?

Upon arrival it was evident that the Casa da Música, commissioned as a European Culture Capital project, did not belong to the recent crisp white wall Portuguese modernist tradition of say Siza or Aires Mateus Arquitectos. This was a building evidently so poorly maintained (a PPP failure?) that only the strength of the concept lifted the shock of seeing a dirty ‘new’ building. The dirt seemed to result from the concrete shuttering not being in facial plane and thus accumulating urban soot. Was this the fault of the architect or the contractor? Porto or the EU? Such concerns are irrelevant when the old traditional houses opposite Casa da Música’s front door are also in a state of extreme degradation. A contextual empathy? Heck, Porto is a great city and all great cities have the ‘authenticity of dirt’: Istanbul, Berlin, Brussels, even Hackney. If these cities are grimy why should contemporary architecture be so purile? Dirt adds value (and music recognises this in its genres: rock, grime, dirty house). Yet the historic European city has a patination which appears to be at odds with emerging urban aspirations. The shiny new world cities which frequently top the Economist Intelligence Unit’s list of best city to live in such as Toronto, Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland are all gloss, no grit.

Back in London we wondered what if Rem had decided to use a Brutalist material palette to confront the weathered city? Rough cast concrete as evident in Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Nantes (where one can stick their fist in the hole-in-a-wall due to a dry concrete mix) or, next to our Old St office, rough cast like the Barbican. We imagined a Casa da Música brutally remixed by WHAT_architecture where dirt was celebrated not as an aesthetic (Adjaye’s Dirrty House) but as an actuality of urbanism.

132nnr_Balcony Fishing

With many people living in towns and cities, this housing project embraces urban fishing. Fishing from your inner-city balcony requires little equipment and its provides many advantages to fishing in rural areas. Standard canal fishing tactics include a light tackle as there is a lot of debris on the bottom of the canals around Hackney and getting snagged can be a pain. Float fishing works as does making use of any features such as moored boats, Venetian gondolas, maori war canoes etc. Organic bait that can be cultivated on your balcony includes: maggots, worms, sweetcorn and, er, hemp. Small spinners will catch perch and shallow diving plugs/lures can catch some of the many pike in Regent’s Canal.

00off_ÇEVRE DUYARLI MİMARLIK!

Thanks to Dr. Serpil Çerçi of Çukurova Üniversity, Shoreditch Station features as an example of ‘çevre duyarli mimarlik’ or environmentally sensitive architecture in the 50th anniversary edition of Mimarlik, the Turkish architectural magazine.

The theme of çevre duyarli mimarlik, is increasingly important given the rapid pace at which the Turkish government has launched urban redevelopment projects. The prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has promised an array of mega-projects including a 25-mile canal between the Black and the Marmara seas as well as two new cities on both sides of the Bosporus, each housing at least 1 million people – the centre of his election campaign.

“We need to face it,” Topbas said in a press conference after the devastating 2011 earthquakes in Van that killed 644 people, “we need to rebuild the entire city.”

Now the Turkish government is preparing a new law that will grant the prime minister and the public housing development administration sole decisive power over which areas will be developed, and how. The law will overrule all other preservation and protection regulations, and allow the government to declare any area in Turkey a zone of risk. Affected house-owners will have the choice of either demolishing their buildings themselves, or letting the government do it for them – in exchange for compensation. The law’s advocates argue that it will enable the government to make cities safer against the ever-present risk of earthquakes without a lengthy legal process. However, a growing number of critics point out that it will serve as a pretext to open valuable land to speculation, and drive low-income groups from city centres.

And the government’s appetite for ever more ambitious development projects is not likely to be sated in the near future. According to the Turkish Contractors Association’s predictions, the construction sector, which contributes about 6% to the economy, faces decline and much fiercer competition abroad in 2012: domestic urban renewal projects, estimated to generate £250bn of profit – £55bn in Istanbul alone – are seen as a convenient alternative. Professor Gülsen Özaydin, head of the urban planning department at the Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts Istanbul, says: “There is no urban planning that sees the city as a whole. Projects are completely detached from one another, and take no heed of the existing urban fabric, or the people living there. That’s very dangerous for the future of a city.”

According to Resistanbul, the demolition of Gezi Park – the issue which sparked the current protests – is a part of a wider urban redevelopment project in Istanbul that includes building a shopping centre which Erdogan says would not be “a traditional mall”, but rather would include cultural centres, an opera house and a mosque. The plan also includes rebuilding an Ottoman-era military barracks near the site and demolishing the historic Ataturk Cultural Centre and some see this as having historic symbolism, as the barracks were the cradle of a pro-Islamic, pro-Ottoman mutiny in 1909.