171leg_ALPHABET CITY

We await the Jong remix of ‘Seoul Meets London’ for the forthcoming Barbican workshop 171leg_Legobusier…

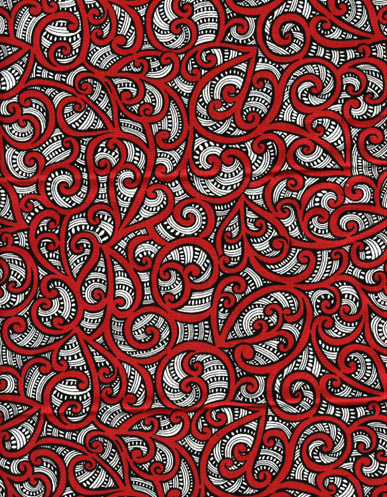

072hin_MODERN MAORI MOTIF

Some cultures have visual motifs so specific, so readily identifiable in their iconography that the motif is intertwined and inseparable from that culture’s history. When a motif is omnipresent, it is a cultural logo. So what is specific about the South Pacific? Polynesian patterns derive from traditional craftsmanship that use simple forms (circles, triangles, lines…) and often applied ‘folk’ styles of decoration. What the folk? Folk is according to Wiki: “art produced from an indigenous culture or by peasants or other laboring tradespeople.” Much like the English Arts and Crafts Movement of (East London’s) William Morris, polynesian folk decoration in its hand appliqué was essentially pre-industrial. Such motifs can be found on tapa cloth, tukutuku panels, as tattoo / tä moko and include köwhaiwhai, koru… In modernising its motif, maori culture is at once enhanced yet evolving. Motif modernisation allow new identities to be created to engage and embrace emergent communities such as the Ngati Ranana London-based diaspora. In the transfer from industry to information, craft becomes crafty. Folk today means ethnicity; the example could have been African, Turkish, Maori…

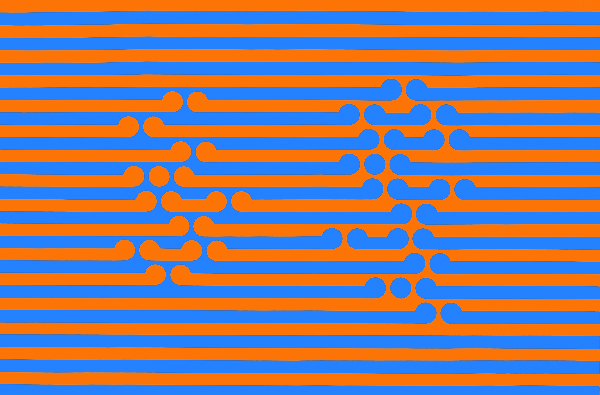

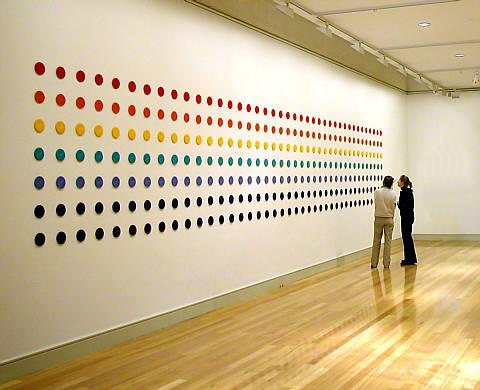

MAORI EXAMPLE: There are a number of visual artists who are confronting the modernisation of traditional maori motif. For the NZ artist Gordon Walters, the koru motif was his way of making sense of the environment and reflected the obvious influence of köwhaiwhai and tä moko. Walters’ koru paintings can thus be understood as a profound meeting of Polynesian and European art traditions, where the value of each is upheld. In the image below WHAT_archutecture renders Walter’s 1965 Painting No. 1 in Hinemihi’s original orange-blue colours that were ‘uncovered’ by Dean Sully of the UCL’s Institute of Archeology. More recently Ani O’Neill is a Rarotongan New Zealander of Irish descent whose works of art frequently reference the traditional Pacific arts of lei, weaving, crochet and tivaevae (appliqué). In discussing her work O’Neill has said that “when you stood in the room the circles had an eye-popping, decentralising effect, they made your eyes bounce around… I grew up with a heritage of bright colours, flowers, feasting, sunshine, lagoons… I’m bringing that culture into a developed New Zealand culture that is primarily about progress.”

Johnson Witehira‘s digital kowhaiwhai;

Some cultures have visual motifs so specific, so readily identifiable in their iconography that the motif is intertwined and inseparable from that culture’s history. When a motif is omnipresent, it is a cultural logo. So what is specific about the South Pacific? Polynesian patterns derive from traditional craftsmanship that use simple forms (circles, triangles, lines…) and often applied ‘folk’ styles of decoration. What the folk? Folk is according to Wiki: “art produced from an indigenous culture or by peasants or other laboring tradespeople.” Much like the English Arts and Crafts Movement of (East London’s) William Morris, polynesian folk decoration in its hand appliqué was essentially pre-industrial. Such motifs can be found on tapa cloth, tukutuku panels, as tattoo / tä moko and include köwhaiwhai, koru… In modernising its motif, maori culture is at once enhanced yet evolving. Motif modernisation allow new identities to be created to engage and embrace emergent communities such as the Ngati Ranana London-based diaspora. In the transfer from industry to information, craft becomes crafty. Folk today means ethnicity; the example could have been African, Turkish, Maori…

MAORI EXAMPLE: There are a number of visual artists who are confronting the modernisation of traditional maori motif. For the NZ artist Gordon Walters, the koru motif was his way of making sense of the environment and reflected the obvious influence of köwhaiwhai and tä moko. Walters’ koru paintings can thus be understood as a profound meeting of Polynesian and European art traditions, where the value of each is upheld. In the image below WHAT_archutecture renders Walter’s 1965 Painting No. 1 in Hinemihi’s original orange-blue colours that were ‘uncovered’ by Dean Sully of the UCL’s Institute of Archeology. More recently Ani O’Neill is a Rarotongan New Zealander of Irish descent whose works of art frequently reference the traditional Pacific arts of lei, weaving, crochet and tivaevae (appliqué). In discussing her work O’Neill has said that “when you stood in the room the circles had an eye-popping, decentralising effect, they made your eyes bounce around… I grew up with a heritage of bright colours, flowers, feasting, sunshine, lagoons… I’m bringing that culture into a developed New Zealand culture that is primarily about progress.”

Johnson Witehira‘s digital kowhaiwhai;

Modern computer-aided drafting systems use vector-based graphics to achieve a precise radius and can also be used to generate a set of coordinates that accurately describe an arbitrary curve. Such digital drawing systems make use of Bézier splines which allow a curve to be bent in real time on a display screen to follow a set of coordinates, imitating the analogue method of drawing arcs and spirals using French curves:

Modern computer-aided drafting systems use vector-based graphics to achieve a precise radius and can also be used to generate a set of coordinates that accurately describe an arbitrary curve. Such digital drawing systems make use of Bézier splines which allow a curve to be bent in real time on a display screen to follow a set of coordinates, imitating the analogue method of drawing arcs and spirals using French curves:

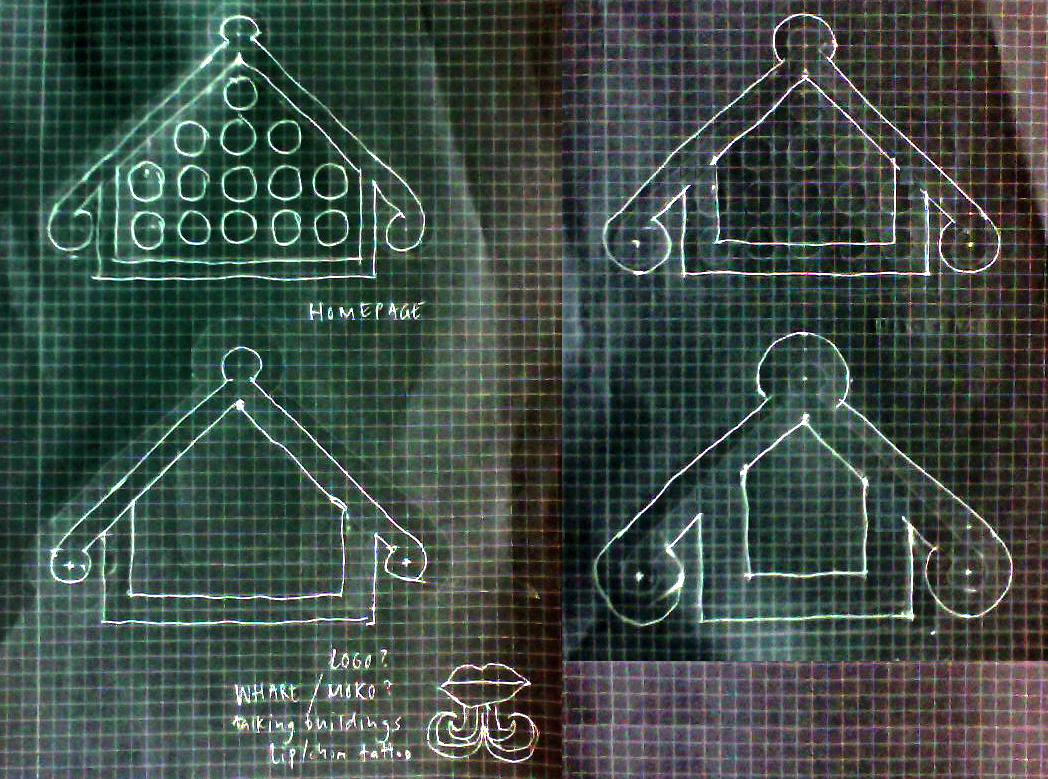

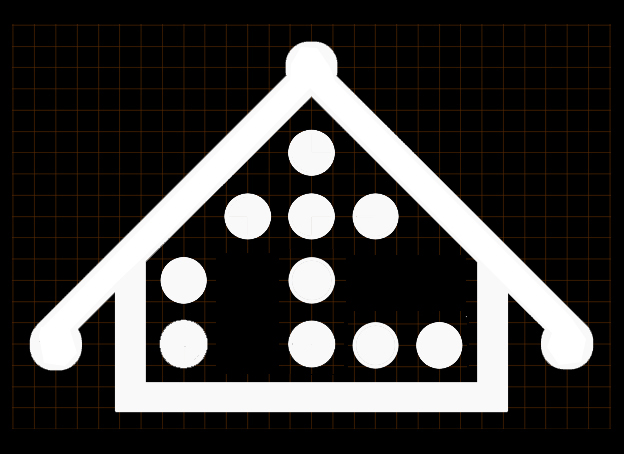

Influenced by such abstract interpretations, it is now possible to reconsider the iconography of maori meeting house Hinemihi in terms of the structure, geometry and fenestration.

Influenced by such abstract interpretations, it is now possible to reconsider the iconography of maori meeting house Hinemihi in terms of the structure, geometry and fenestration.

000off_WHAT_architecture plays Templehof

»DESIGN IS THE NEW WAY OF DOING BUSINESS«

DMY Berlin is an international design network for contemporary product design (yes, even architecture is construed as a consumer product). DMY was held at Templehof, once a part of Albert Speer‘s gateway to Europe and a symbol of Hitler’s “world capital” Germania, and described by Norman Foster as “the mother of all airports”. WHAT_architecture presented ‘2ManyArchitects’…

»Designing Business« at DMY2012 reflected upon the relevance and current role of design in the context of contemporary economics. Rather than providing a manual for building a successful start-up business, it is concerned with the potential of design and design thinking to shape economic and social processes. Is design ›the new way of doing business‹? What trends and tendencies occur today? Is it true that anybody can be a designer today? Crikey if Kanye West and Brad Pitt can be architects, can architects become rappers or even actors? With this leg of our 2012 European Tour, architecture is presented as the new rock ‘n roll.

Under the conditions of continuous change and increasing complexity that define today’s world, the rules that operate and regulate our society and economy change with great rapidity. Against the dramatic backdrop of environmental disasters, demographic change and economic crisis it is becoming clear that the conventional means of conducting and operating »business« has become increasingly ineffective. For this reason, it is important to conceive of new ways of thinking and acting, of analysing problems and turning problems into opportunities. Design and design methods play a central role when it comes to solving complex problems and creatively addressing the challenges of the present and future.

»DESIGN IS THE NEW WAY OF DOING BUSINESS«

DMY Berlin is an international design network for contemporary product design (yes, even architecture is construed as a consumer product). DMY was held at Templehof, once a part of Albert Speer‘s gateway to Europe and a symbol of Hitler’s “world capital” Germania, and described by Norman Foster as “the mother of all airports”. WHAT_architecture presented ‘2ManyArchitects’…

»Designing Business« at DMY2012 reflected upon the relevance and current role of design in the context of contemporary economics. Rather than providing a manual for building a successful start-up business, it is concerned with the potential of design and design thinking to shape economic and social processes. Is design ›the new way of doing business‹? What trends and tendencies occur today? Is it true that anybody can be a designer today? Crikey if Kanye West and Brad Pitt can be architects, can architects become rappers or even actors? With this leg of our 2012 European Tour, architecture is presented as the new rock ‘n roll.

Under the conditions of continuous change and increasing complexity that define today’s world, the rules that operate and regulate our society and economy change with great rapidity. Against the dramatic backdrop of environmental disasters, demographic change and economic crisis it is becoming clear that the conventional means of conducting and operating »business« has become increasingly ineffective. For this reason, it is important to conceive of new ways of thinking and acting, of analysing problems and turning problems into opportunities. Design and design methods play a central role when it comes to solving complex problems and creatively addressing the challenges of the present and future.