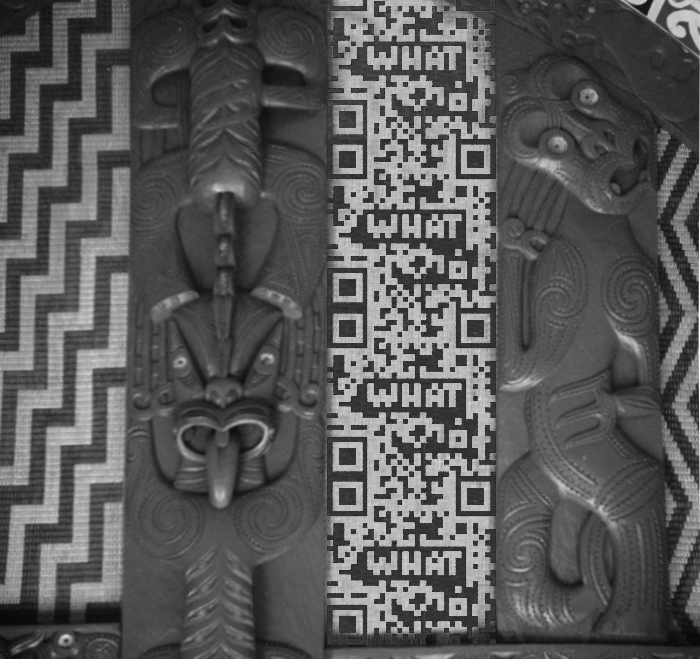

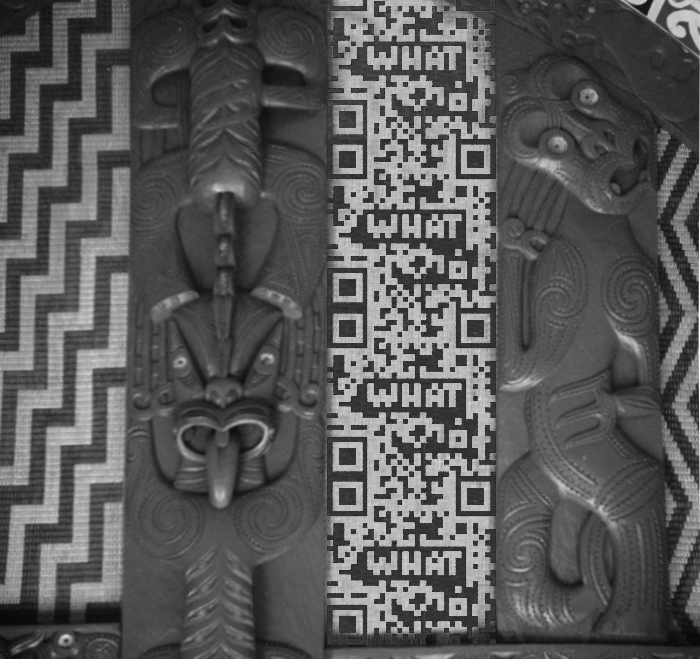

086tho_QR code tukutuku panels

Tukutuku panels could embrace QR codes such that the viewer has an instantaneous virtual museum guide. In doing so, the traditional fuses with the digital.

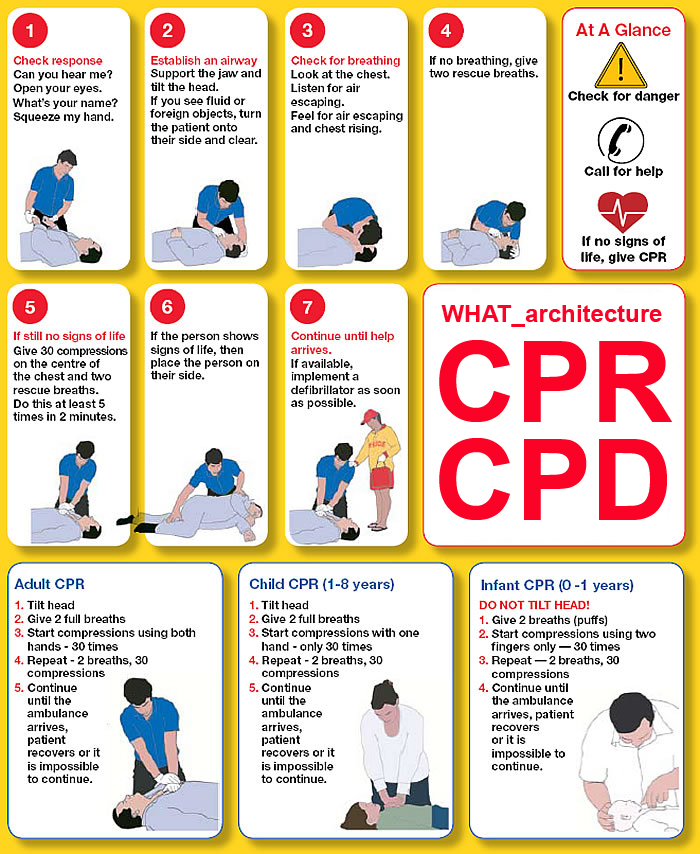

000off_CPR CPD

In the wake of two events of the past week, footballer Fabrice Muamba’s cardiac arrest at White Hart Lane and a sprawled cyclist receiving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on Kingsland Road, it’s time to get back to basics with Continuing Professional Development.

127sho_SIGNAL BOX?

127sho_Shoreditch Overground.

If form follows function, what happens when the intended purpose of a space becomes obsolete? When a building’s use is no longer required? Does form follow function out the door? Let’s look at another brick station for answers. Bankside Power Station closed in 1981 due to rising oil prices and after 29 years of providing power. Then after 19 years of inactivity the building reopened as the Tate Modern in 2000 and 13 years later, it is fair to say, the buildings ‘second life’ as an artspace has triumphed its original purpose.

The social theorist Baudrillard would describe a building that loses its use as a signifier. A hollow space containing only symbols of a former existence. Shoreditch Station without the railways is ironically just ‘a signal box’. A loss of original use does not however have to signal a loss of value so, with a headnod to English Heritage’s ‘logical approach to the historic environment’ our SoS identifies that whilst the station has no historic, evidential or architectural value, it does retain a communal value. And it was for this reason we argued that the former station, less a building than a chattel, should be elevated on top of the new development.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

For Shoreditch Station, the proposal to elevate the station to a higher ground is made meaningful when we realise that the ground beneath the station’s feet has already been swept away. The railway tracks and double-height vaulted walls were demolished to make way for the East London extension. The UCL Institute of Archeology has suggested that the station was never a building after all, as it is without foundations (the station structure sits on 6 steel beams spanning over non-existent platforms and tracks: the station’s purpose was derailed some time ago by TfL. So today the station sits above hollow ground, as a signifier of a time when it was once a station. A ghost building for ghost trains.

The story of Shoreditch Station is not only one of recession but also optimism. It needs to have a use that, like the neighbourhood it is situated in, is diurnal. Yet unlike the current scenario in Brick Lane, the station’s future use requires a diurnality that is not a fast-speed schizophrenia between daytime-shopping and nighttime-drinking, a slower space that embraces art and housing. Housing normalises a neighbourhood saturated with entertainment licences. And art , as evident in the streets and on the station, can provide new signs of tomorrow. Shoreditch Station already has an accidental new use as a focal point along street art tours. Whether the heritage vs art house strategy is manifest as old crowning the new, or it’s polar opposite, new bearing down on the old, it doesn’t really matter as long as there are both signs of the past and future omnipresent.

127sho_FROM A RAILWAY STATION TO AN ARTS SPACE

The former Shoreditch Station is not a building but a ‘chattel’. This seemingly perverse claim is rendered plausible when one recognises that the former Shoreditch Station is a building without foundations: it is a structure that straddles a series of steel beams that span what was once the now non-existent railway tracks. English Heritage recognise this when rejecting a listing of the station in 2002. So whilst the former station has little heritage, aesthetic or scientific merit, the Statement of Significance submitted with our Planning Application does appreciate that the station holds a social significance in the collective consciousness. A nostalgia for the railways and Britain’s industrialisation of transport is alive – Railway Magazine will hold their annual dinner in the former station! So whilst the building has lost use and effectively become a ghost train, it’s elevation to crown to the proposed development demands an inspired new use .

So what next? It is often said that East London is home to the greatest concentration of artists in Europe. Whilst the urine alleyway that is ‘piddley street’ mighty require the normalisation that housing allows, the WHAT_development proposal offers three floors of artspace. In some way the transformation of the building from an infrastructural use to the arts maps that of the Tate Modern and many other obsolete spaces that the creative mediums now invigorate. Of course, the penthouse ought not be for private use – a banker’s bachelor pad – but for the community. With this in mind consultations have begun with the arts charity Spitalfields Music. Their remit of education through music would be a perfect head tenant for the elevated station. Spitalfield Music’s privileging of the analogous over the digital, of man over the machine, can also be seen Shlomo’s The Vocal Orchestra

165sei_Istanbul: Super Seismic Me!

WHAT_ are we doing trying to design for seismic risk In Istanbul?

Istanbul houses about 20% of the total Turkish population and 50% of it’s industrial potential. And note: Turkey was the world’s second fastest growing economy after China recording 11.7% growth in Q1 of 2010. Besides a very high earthquake hazard, the earthquake risk in the city has increased due to overcrowding, faulty land-use planning and construction, inadequate infrastructure and services and environmental degradation. Following the losses suffered during the two major earthquakes that struck Turkey in 1999, there has been a broad recognition of the need for extensive earthquake preparedness and response planning based on detailed earthquake risk analysis in Istanbul… furthermore the average return period for ‘stress fracture’ related earthquakes (i.e. the occurrence of an earthquake on one fault has an impact on the probability of occurrence on another fault) in this region is 50 years.

Today its 2012 so a sizeable earthquake is likely to occur within the next 37 years. We don’t know how old you are but I hope to be alive at that time watching grandchildren kick balls for, or against, Fenerbahçe. This project seeks to use the creative latitude of architecture to engage in what is ordinarily considered an engineering problem for societal gain.

128art_TALKING BUILDINGS: FAÇADE TAGGING IN THE INFORMATIONAL AGE.

Local Authority Partnering Guidelines are being drafted by WHAT_architecture in response to receiving a LBTH Defacement Notice from the Council in late 2011. This notice was served because a “Sign/Graffiti’ (informal or illegal marks, drawings or paintings) have been deliberately made known” and that this is “a blight on the local environment which the Council considers to be detrimental to the amenity of the area or offensive.”

So what does the Council consider detrimental or offensive? The Council’s own website clarifies the latter as being either racist or obscene. Fair cop there. Regarding detriment, then this is a concept relative to context. It’s difficult to say that non-offensive graffiti is detrimental to a pissoir alleyway locally referred to as ‘piddle street’. The council is however concerned about the ‘knock-on’ effect of graffiti: street art which could inspire tagging. And tagging is not only bad but it’s banal. However associating one event on another is akin to suggests that watching Terminator might lead one on a copy-cat gun-rampage. The ‘broken windows theory’ described by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling asks us to “consider a building with a few broken windows. If the windows are not repaired, the tendency is for vandals to break a few more windows. Eventually, they may even break into the building, and if it’s unoccupied, perhaps become squatters or light fires inside. Or consider a sidewalk. Some litter accumulates. Soon, more litter accumulates. Eventually, people even start leaving bags of trash from take-out restaurants there or breaking into cars.”

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: graffiti. The etymology of the word graffiti derives from the Italian graffito (meaning “scratched”) where designs were scratched or inscribed into a surface. The earliest forms of graffiti date back to 30,000 BCE in the form of prehistoric cave paintings and pictographs using tools such as Animal bones and pigments. These illustrations were often placed in ceremonial and sacred locations inside of the caves. The images drawn on the walls showed scenes of animal wildlife and hunting expeditions in most circumstances.

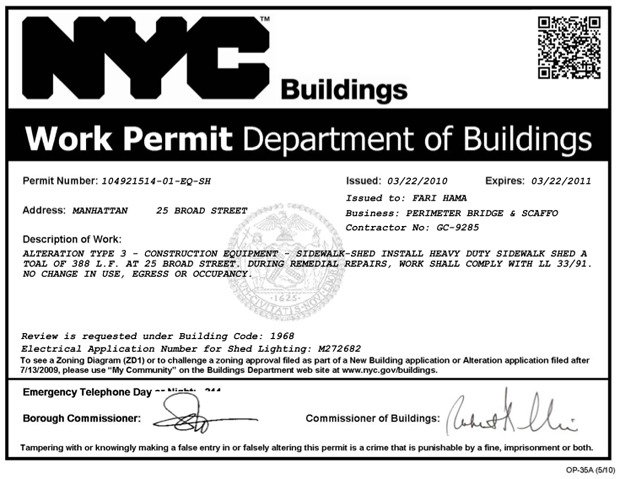

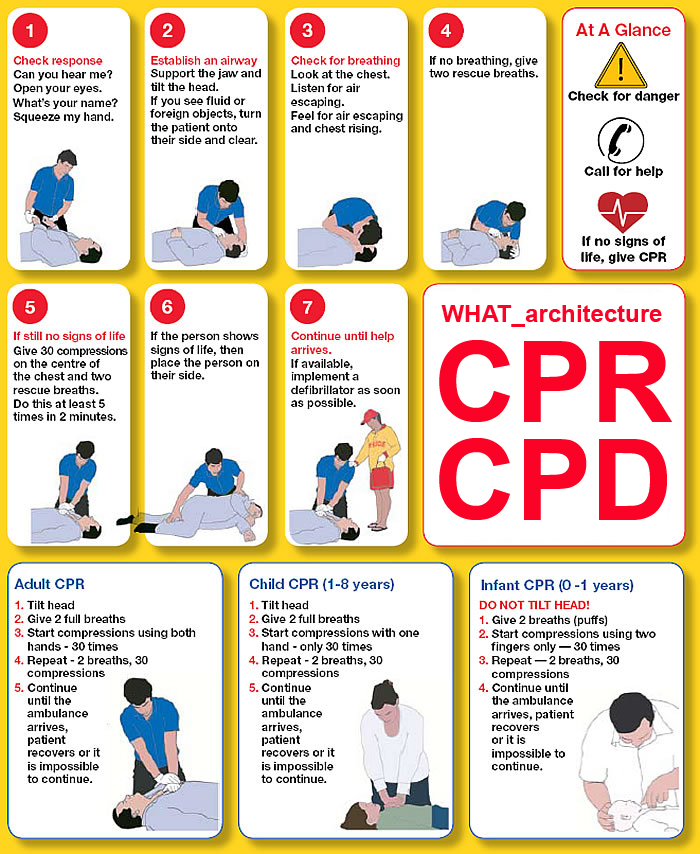

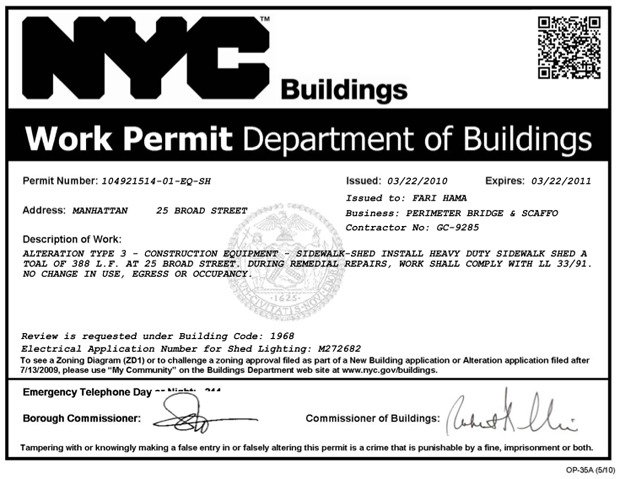

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: QR codes. QR Codes are being used to facilitate planning protests by embedding meta-data and text into physical spaces. In 2011, New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg unveiled a system of QR tags meant to give citizens quicker access to information about new construction projects. The QR codes are posted on every construction permit city-wide; by downloading a QR reader app on any smartphone, city-goers can scan these codes to see a web view of what’s being built, who is doing the building, and what (if any) complaints have been filed against the applicant. C’mon London: printing QR codes on Public Notices costs the Local Authority nothing… but engages wider public opinion!

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: graffiti. The etymology of the word graffiti derives from the Italian graffito (meaning “scratched”) where designs were scratched or inscribed into a surface. The earliest forms of graffiti date back to 30,000 BCE in the form of prehistoric cave paintings and pictographs using tools such as Animal bones and pigments. These illustrations were often placed in ceremonial and sacred locations inside of the caves. The images drawn on the walls showed scenes of animal wildlife and hunting expeditions in most circumstances.

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: QR codes. QR Codes are being used to facilitate planning protests by embedding meta-data and text into physical spaces. In 2011, New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg unveiled a system of QR tags meant to give citizens quicker access to information about new construction projects. The QR codes are posted on every construction permit city-wide; by downloading a QR reader app on any smartphone, city-goers can scan these codes to see a web view of what’s being built, who is doing the building, and what (if any) complaints have been filed against the applicant. C’mon London: printing QR codes on Public Notices costs the Local Authority nothing… but engages wider public opinion!

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: graffiti. The etymology of the word graffiti derives from the Italian graffito (meaning “scratched”) where designs were scratched or inscribed into a surface. The earliest forms of graffiti date back to 30,000 BCE in the form of prehistoric cave paintings and pictographs using tools such as Animal bones and pigments. These illustrations were often placed in ceremonial and sacred locations inside of the caves. The images drawn on the walls showed scenes of animal wildlife and hunting expeditions in most circumstances.

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: QR codes. QR Codes are being used to facilitate planning protests by embedding meta-data and text into physical spaces. In 2011, New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg unveiled a system of QR tags meant to give citizens quicker access to information about new construction projects. The QR codes are posted on every construction permit city-wide; by downloading a QR reader app on any smartphone, city-goers can scan these codes to see a web view of what’s being built, who is doing the building, and what (if any) complaints have been filed against the applicant. C’mon London: printing QR codes on Public Notices costs the Local Authority nothing… but engages wider public opinion!

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: graffiti. The etymology of the word graffiti derives from the Italian graffito (meaning “scratched”) where designs were scratched or inscribed into a surface. The earliest forms of graffiti date back to 30,000 BCE in the form of prehistoric cave paintings and pictographs using tools such as Animal bones and pigments. These illustrations were often placed in ceremonial and sacred locations inside of the caves. The images drawn on the walls showed scenes of animal wildlife and hunting expeditions in most circumstances.

Talking buildings. Or rather buildings that talk to you: QR codes. QR Codes are being used to facilitate planning protests by embedding meta-data and text into physical spaces. In 2011, New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg unveiled a system of QR tags meant to give citizens quicker access to information about new construction projects. The QR codes are posted on every construction permit city-wide; by downloading a QR reader app on any smartphone, city-goers can scan these codes to see a web view of what’s being built, who is doing the building, and what (if any) complaints have been filed against the applicant. C’mon London: printing QR codes on Public Notices costs the Local Authority nothing… but engages wider public opinion!